Katherine Gaffney Wins 2022 Tampa Review Prize

Katherine Gaffney has won the 2022 Tampa Review Prize for Poetry for her collection, Fool in a Blue House. In addition to a $2,000 check, the award includes hardback and paperback book publication in 2023 by the University of Tampa Press.

Katherine Gaffney holds an MFA from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and is currently working on her PhD at the University of Southern Mississippi. Her work has previously appeared in jubilat, Harpur Palate, Mississippi Review, Meridian, and elsewhere. She has won the Mississippi Review Poetry Prize among others and has attended the TinHouse Summer Writing Workshop, the SAFTA Residency, and the Sewanee Writers Conference as a scholar. Her first chapbook, Once Read as Ruin, was published by Finishing Line Press.

Tampa Review judges praised Gaffney’s collection, stating:

“When Katherine Gaffney’s speaker refers midway through her collection to what is ‘Long precedented/ in defense of choice’, she reminds us that only a few poets can truly predetermine the conditions for their own arrival. Yet, inchoosing this extraordinary year-spanning Fool in a Blue House as the winner of the Tampa Review Prize for Poetry, we were struck by Gaffney’s intense working between curation and assurance, this against the poetic life and body in its ongoing amendments of scale. Gaffney, in ranging us from medieval deconstructions of the heart, through to the near-apocalyptic radicalisation of the domestic, produces a book so exceptionally alive, wild, tense, and learned as to announce Gaffney as a pre-formed, right-here, right-now major new voice in American poetry, her speaker ‘a denounced planet’ only so denounced because the shadow of its prefigurement is about to cast wide. Fool in a Blue House is as much a collection of poems as it is a process of intimate discovery—intimacy in relation to love in all its facets and subsequent relationships. The poems wrestle with inheritances of gender and seek fissures for growth beyond that inheritance.”

“Most of these poems unfurled during a time of intense evolution in my understandings of romantic and familialrelationships,” Gaffney says. “The poems seek to reconcile the tectonic shifts involved with those kinds of relationships as we, as humans, move through time and space.”

This year the judges also announced four finalists:

Fabula by Supritha Rajan

Late Bloomers: a Documentary Film by Roman Gibbs by Chuck Sweetman

Rituals Unbound by Johnson Cheu

Somehow Holier by Joshua Jones

The Tampa Review Prize for Poetry is given annually for a previously unpublished book-length manuscript. Judging is by the editors of Tampa Review.

Submissions are now being accepted for 2023.

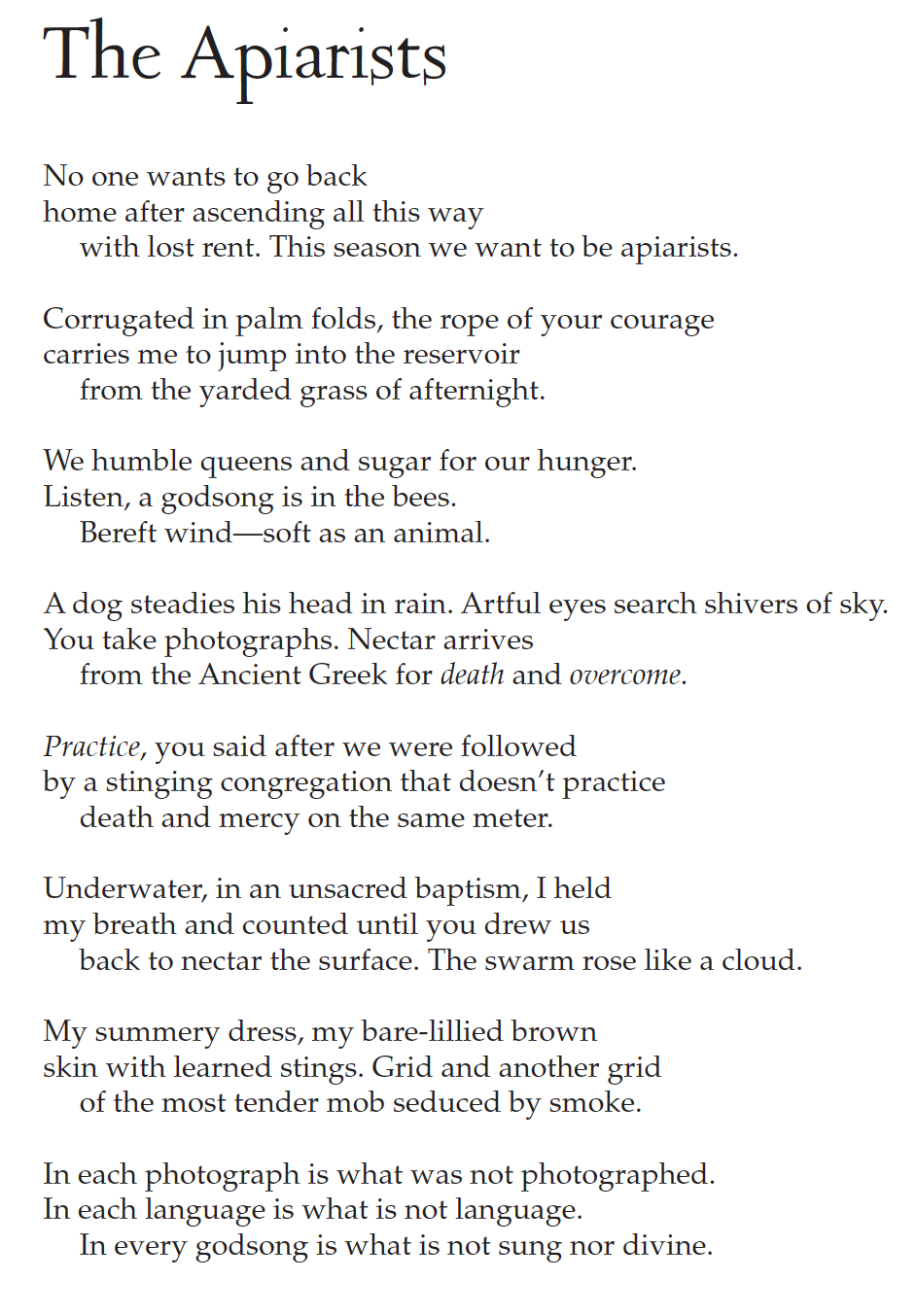

Congratulations to Jai Hamid Bashir, whose poem “The Apiarists,” which appears in

Congratulations to Jai Hamid Bashir, whose poem “The Apiarists,” which appears in

Tampa Review wishes to congratulate Mary-Alice Daniel, who has just won

Tampa Review wishes to congratulate Mary-Alice Daniel, who has just won

Born and raised in Providence, Rhode Island, Keith Kopka spent many years playing in and touring with punk and hardcore bands all over the country. His poetry and criticism have recently appeared in Best New Poets, Mid-American Review, New Ohio Review, Berfrois, Ninth Letter, The International Journal of The Book, and many others. Formerly the Managing Director of the creative writing program at Florida State University, he is also the author of the critical text, Asking a Shadow to Dance: An Introduction to the Practice of Poetry (Great River Learning, 2018), and the recipient of the International Award for Excellence from the Books, Publishing, & Libraries Research Network. Kopka is a Senior Editor at Narrative Magazine, the Director of Operations for Writers Resist, and an Assistant Professor at Holy Family University in Philadelphia. The following are two poems from his collection Count Four., available from the University of Tampa Press:

Born and raised in Providence, Rhode Island, Keith Kopka spent many years playing in and touring with punk and hardcore bands all over the country. His poetry and criticism have recently appeared in Best New Poets, Mid-American Review, New Ohio Review, Berfrois, Ninth Letter, The International Journal of The Book, and many others. Formerly the Managing Director of the creative writing program at Florida State University, he is also the author of the critical text, Asking a Shadow to Dance: An Introduction to the Practice of Poetry (Great River Learning, 2018), and the recipient of the International Award for Excellence from the Books, Publishing, & Libraries Research Network. Kopka is a Senior Editor at Narrative Magazine, the Director of Operations for Writers Resist, and an Assistant Professor at Holy Family University in Philadelphia. The following are two poems from his collection Count Four., available from the University of Tampa Press: