Photo by Dave Anderson

J. Malcolm Garcia has contributed to Tampa Review for more than a decade, bringing us vivid and memorable portraits of people, places, and problems from around the world. Two of his new pieces—one from Bangladesh and the other from Guatemala—are forthcoming in Tampa Review 57/58, a special double-issue due to be released in late Spring. Garcia is a global freelance journalist, recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism. His work has been anthologized in Best American Travel Writing, Best American Essays, and Best American Nonrequired Reading. He is also the author of four books, Without a Country: The Untold Story of America’s Deported Veterans, The Khaarijee, What Wars Leave Behind, and most recently Riding through Katrina with the Red Baron’s Ghost.

Malcolm suprised me with a recent email from Viet Nam, a trip that we had not seen coming. The details and impressions he included evoked a street-level sense of current life there that seemed worth sharing. With his permission, I’m posting it here on Tampa Review Online, where it can offer a glimpse of a place that few of us will have a chance to visit, though it is a country that looms large in American awareness. From his encounter with a fast-talking huckster at the Hanoi airport to his unexpected stranding at a village outside Da Nang in the middle of the night, when a bus driver decides not to finish his trip, Garcia reports some of the personal circumstances that frame and impact his travel.

Though his letter ends without resolving his bout with dengue virus, I am happy to report that he has made it safely home, without a fever!

– Richard Mathews

========================================================================

Hey Richard,

I arrived in Hanoi a little before midnight on the 6th of February. A driver from the hotel was supposed to pick me up, but he never showed. A guy in the airport lobby flashed me a badge, said he managed drivers, and offered to arrange a lift. I thought something wasn’t quite right, but I was tired after 22 hours of travel and I went along. He took me up three flights to an obscure part of the Hanoi airport and called a car. That, I thought, was also strange. When the car came, he got in with me. Strange number 3. Why would he get in with me if he makes his money calling cars for customers at the airport? Shouldn’t hestay at the airport? But we set off. When we approached a toll he asked to see all my money so he (I) could pay for it. That’s it, I thought, and got out of the car in the middle of nowhere—Hanoi, after midnight. I began trudging back to the airport to get a real taxi. One passed me after fifteen minutes or so and took me to the hotel.

The next morning, I explored the city as I waited for a friend, Darren, a photographer, to meet me at the hotel. He took a separate flight from Boston about 24 hours after I left my home in San Diego and we’ll be traveling together. I dove into the local cuisine: snail and ramen noodles for breakfast. Hanoi has no traces of the war, which makes sense after 45 years. It’s an old city with old French colonial buildings. Young people don’t know much about the war, called here “the American War.” One American vet who lives in Hanoi has PTSD, which shows itself in his obsession with the war. He reads as many books as he can about it.

I did see the Hanoi Hilton. The biggest impression it made on me was the image of a tourist in the gift shop trying on sandals, asking about sizes, etc. That’s what the POW camp has become—just another tourist attraction surrounded by tall apartment complexes. Empty prisons don’t really give a sense of the horror that went on there. But a guy trying on sandals tells you how far in the past that horror is.

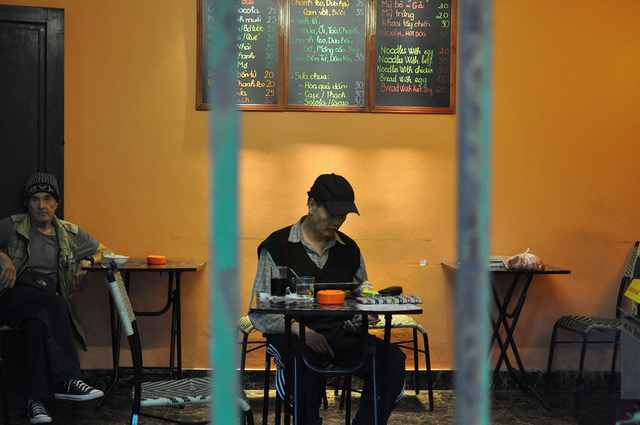

Once Darren arrived, we left Hanoi and took a bus to Da Nang. The buses have the equivalent of bunk beds, so you get to sleep. We left at 6 p.m. and arrived in the town of Hue at 4 a.m., about an hour and a half away from Da Nang. The driver kicked us out. Not enough passengers in his view to go the rest of the way. So, we sat on a doorstep for four hours until a bus company opened to take us the rest of the way. We were going to hitch, but the light at that obscene hour was great for taking pics and I enjoyed watching the street vendors slowly filter out to set up shop. Instead of hitching, we took our stranded hours as an opportunity to explore.

Da Nang is like Dubai. It has become very glitzy and Westernized. I hung with vets here and met vets who had come to visit sites where they had served and to make peace with whatever they needed to make peace with. It was interesting to watch them open up and hear all the memories, many horrible, that poured forth. Hearing them has been helpful to me to sort out some of my experiences in Afghanistan.

We were going to go and visit vets in Saigon, far to the south, but that didn’t quite work out. We went to catch our train, and despite having tickets, we had no seats. The only seat they offered us was one plastic chair no bigger than what a kid would sit in at a daycare center, positioned smack dab in front of the bathroom. The train was filthy and the bathroom defied all my previous bathroom experiences as mere elective courses for earning a degree in what a real shitty shiter is. The idea for the kid’s chair was that the photographer, Darren, and I presumably were supposed to alternate between sitting and standing for 22 hours. I laughed at the absurdity. Darren lost it. At one point he shouted, They wouldn’t even do this in Afghanistan!! That only made me laugh more. He and I worked together in Kabul in 2003 and 2004.

Back in Da Nang, I met a Vietnamese guy who had been “adopted” by Marines back in the war when he was nine. He basically was the errand boy. Now he’s 61, and you can see the influence of the Marines because every other word he says is fuck. I introduced myself and he said, “Malcolm? Weird fucking name, man.” We got along quite well.

From Da Nang once more we headed north to Sapa, a once-rural area that now resembles Aspen. The local indigenous people turn out and sell themselves in traditional dress for visitors to pose with, take pics, etc. Their kids, looking like JonBenét Ramsey, cry. They clearly hate being displayed for the pleasure of tourists. And the local farmers have been turned into set pieces for visitors to see “the real” Vietnam. We fought the war allegedly to stop Communism. Little did we know the threat was capitalism.

After Sapa, I returned to Da Nang where I am now to follow up with some vets I met earlier. Here I came down with dengue virus, which for me was like a severe flu. It has not been pleasant. At a pharmacy, a doctor gave me five different meds and asked me to swear that I would take them for a minimum of five days for maximum effect. I swore, raising my right hand. The doctor smiled and said that was not necessary. I followed through taking the medicine for five days and feel much better although I still feel traces of of a cough percolating in my chest.

That’s about it for now. . . . just offering a small glimpse of life here.

Cheers,

Malcolm