by Paul T. Corrigan

Tampa Review Poetry Editor

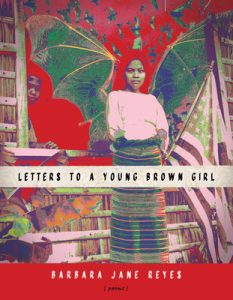

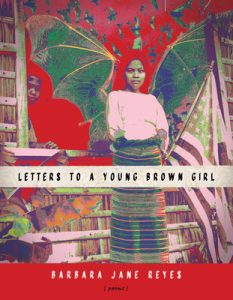

What is it like to be a young brown girl, especially a Filipina immigrant, in the United States? Well, there are pitfalls, attests Barbara Jane Reyes in her latest book of poems, Letters to a Young Brown Girl (BOA 2020), which begins, “If you want to know what we are . . .” (p. 9). But, she hastens to add, fuck the pitfalls and sing your own song. Three of those words—fuck, sing, and you—stand out as keys to understanding the whole book. Letters consists of three sections: a set of prose poems under the heading of “Brown Girl Designation,” a set of free verse poems linked to specific pop songs and assembled as a “Mixtape,” and a set of epistolary poems with the same title as the book, each beginning “Dear Brown Girl.” While only that last section is overtly written as letters, the whole book has an epistolary spirit, central to Reye’s low—even “lowing”—poetics of muck, music, and mutually constitutive interconnections.

The first key word is fuck. In Wanna Peek Into My Notebook? Notes on Pinay Liminality (Paloma 2022), a collection of prose offering insights into her poetics, Reyes lays out the lived context for her use of coarse language in her poems: “The world in which we live, work, and write is messy, and it is full of injustice and violence; it needs us to bring our ruckus. We are at our best when we are scrappy; when we are noisy and unruly, unashamed of profanity, irreverence, and taboo” (p. 35). More specifically, she adds that she wrote Letters “For brown girls who have taken weaponized gender and cultural expectations of white supremacism, and said, Fuck You” (Wanna, p. 134). Appearing and reappearing throughout Letters in various forms the word “fuck” signals a particular poetics at work (pp. 10, 11, 15, 16, 18, 25, 26, 46, 47, 51, and 63).

Reyes unpacks her poetics of fuck in the first “Dear Brown Girl” poem, “[They will say, your language lacks finesse].” In this poem, Reyes invokes a harmful dichotomy of poetry built by those who would degenerate the eponymous brown girl’s words—a dichotomy between a high poetics and a low one. On the one hand, Reyes explains, “they” will claim “their well-lit high poetic annals” (p. 51). Consisting of canonical poems written primarily by white men, those annals value such formal literary qualities as elegance, complexity, and finesses—formal qualities that the brown girl’s words, on the other hand, are said to lack. “Dear Brown Girl, / They will say, your language lacks finesse, your words low . . . you are simple, making inelegant noise. You are lowing” (p. 51). Her use of the word lowing, the sound cows make, followed by reference to the addressee as “some brown cow,” indicts a sexist, fatphobic commonplace (p. 51). But “they,” the poemsplainers, are not just wrong to use the slur, they are also wrong about poetry. “High” formal qualities are not the only way to write poems. To the contrary, “you” have reasons to write differently. “You” have reasons to write poems that may be (perceived as) “coarse,” “beastly,” “monster[ous],” “hollar[ing]” (p. 51). “You” purposefully write with a different set of formal qualities to accomplish a definite function. “You” write to resist. But, with a sudden shift of pronouns, you becoming I, they addressed as you, Reyes speaks back to “them” directly: “My noise is inelegant, because I’m throwing f-bombs at you, motherfucker” (p. 51).

As a poetics, “fuck” speaks to the irreverence necessary to throw off oppressive racial and gender expectations and to tell off those trying to control you. Poetry doesn’t have to be tidy because life isn’t. “Our literature,” Reyes elaborates, “is about how we suffer, work, cope, survive, get gritty and fight, persevere, and celebrate. Then get back to work again . . . this literature exists in the real world, written by real people, working people who live in the real gritty, brutal world” (Wanna, p. 82). In short, “fuck” signifies a poetics of ruckus and reality. It’s about agency, resistance, recognition of what’s what. It’s about asserting one’s own language on one’s own terms. The poetics of fuck rejects control dressed up as decorum. The poetics of fuck represents an attitude, a stance, and a series of formal choices: a tone of defiance, content reflecting social realism, and a serious engagement with “low” culture, including “profanity,” popular music, letters, and mixtapes—all drawn from and speaking to the muck of real life.

But real life is not only muck. It is also music. The “lowing” of the poems in Letters is song—literally so in “Brown Girl Mixtape,” the middle section of the book, where each poem is titled after a work of popular music, including Mary J. Blige’s “My Life” and Pinay’s “Dahil Sa Iyo” (pp. 30, 34). Mixtape is a low cultural form Reyes specifically contrasts with the forms of “High Literature.” She explains, “A more accessible means of communication for those like me, thwarted by ‘High Literature,’ is the mixtape, where tone/mood, rhythm/music, and lyric intersect in accessible units and media. . . . Before digital music, constructing mixtape was a manual and tactile labor of love. It was DIY. It was gift and keepsake” (Wanna, p. 108). Given the importance of this music in the book and Reyes’s association between music and love, it makes sense that the word sing would be another key to understanding the Letters, appearing in various forms almost as frequently as fuck (pp. 12, 13, 23, 27, 32, 34, 37, 45).

The import of sing to the book as a whole might be most directly heard in one of those mixtape poems: “Track: ‘A Girl in Trouble (Is a Temporary Thing),’ Romeo Void (1984).” The first line of this poem serves as a subtitle—“Brown Girl Sings Whalesong”—while the second introduces another fatphobic slur that “they say,” presumably the same “they” as in the epistolary poem discussed above. “When they say you are as big as a lumpy, blubbery whale,” Reyes begins but then, as with the cow reference, immediately reverses the insult, rejecting white male standards for poems and bodies without ceding an inch of poetry or beauty: “you may go ahead and bellow deep. Creak, / croon, and trill, moan low” (p. 32). In other words, when they go “high,” you low. The remainder of the poem continues in the same direction, celebrating positive aspects of literal whales in ways that take on clear figurative significance: “your heart is larger than a full-grown man. Your lungs carry air for us all. / Your ribcage could be a refuge. Your skull is a cavern of deep song” (p. 32). Whales have an ancient and ancestral connection to water. Whales have long lives and memories. Whales’ bodies (perhaps too much like The Giving Tree) supply oil that lights lanterns. Whales communicate with family through song. The poem ends with another pronoun shift (at least, this does not sound like the same “they” as in the first line) and more singing: “They say the earth’s most unruly parts sing like you” (p. 32). Reclaiming the majesty of the whale as an actual animal, the poem also elevates the whale to a metaphor for a majestic way of being and making music in the world.

In some ways, the poetics of sing might seem the opposite of the poetics of fuck—lifting up what is beautiful rather than knocking down what is awful. But for Reyes the two poetic modes share much in common (including low forms) and exist side by side, as this same whalesong poem shows. Though thirteen of the poem’s lines praise whales, that one hideous body-shaming line remains. The insult of calling a woman a whale is a verbal assault on whales, on women who do not fit the strictures of sexist, racist, classist body ideals, and on figurative language itself, since, on top of everything else wrong with it, it’s a cliche. All that ugly is permanently part of the poem. But by seeing and raising the cliche to actual metaphor, Reyes situates the beauty in the context of and in refutation of the ugly. Such juxtaposition is a built-in part of the poetics of sing. In this poem and throughout the book, the key word sing speaks to the urgency and possibility of raising one’s voice, of being heard, and of making beauty despite everything. Without fuck, the poetics of sing would be sickly sweet, false. But without sing, the poetics of fuck would fall short, beginning and ending with resistance, opposition, defiance. Sing brings in the necessary complements of celebration, beauty, intimacy, grief, love.

Another “low” literary form Reyes uses in Letters is in fact personal letters, the epistolary, which she notes has historically often been “where and when women and girls even have time, space, and permission to write” (Wanna, p. 37). Reyes describes the physicality of writing letters in a way similar to what she says, quoted above, about the physicality of constructing mixtapes. “Before email, before texting,” she explains, “epistolary was a manual and tactile art making. It was handwritten with just the right implement—ink color, nib or point, heft of the thing in your hand—on just the right paper—wide, college, or narrow ruled, grid, weight and texture, color, stationery design—with the right postage stamps—hearts, rainbows, comic book characters, historical figures. All of this speaks to meaningful, high emotional stakes human connection. It also speaks of aesthetics” (Wanna 107). Although Letters does not include literal stationary and stamps, the history of physical letters invoked by the epistolary form helps the book leverage the aesthetics of human connection, most obviously in those poems that begin “Dear Brown Girl” (including the one discussed above) but most pervasively through Reyes’s use of direct address. The second person pronoun “you”—the third key word for understanding Letters—works the epistolary mode into the whole book, with versions of the word appearing on almost every single page of the book (except pp. 31, 35, 44, 59, 37, 40, which use first person).

As noted above, who the word “you” refers to shifts throughout the book. Mostly, “you” refers directly to the young brown girls for and to whom Reyes is literally writing. But “you” can instead refer to those oppressing young brown girls, as in Reyes’s comment about “throwing f-bombs at you” quoted above. Moreover, you might mean “one” (the general you) or even “I” (which we might call the lyric-you). This shifting happens on purpose, as Reyes makes clear when she complicates the word in the poem “Brown Girl Fields Many Questions” on the very first page of the book—shedding light on the larger implications of the second person pronoun for the book and for her poetics as a whole: “the ‘you,’ is really meant to be an ‘I,’ a ‘we,’ regardless of whether the hearer, onlooker, or reader wishes to be included or addressed, . . .” (Letters, p. 9). In this definition, the second person may encompass the first and third persons. Reyes writes of and to an expansive “you”—a “you” inescapably intertwined with others, whether you like it or not.

To understand this conception of “you,” we need to consider the Filipino (Tagalog) concepts of kapwa and loób, about which Reyes writes, “I return to my study, growing understanding, and practice of Filipino core values and concepts which for me become the heart of the matter—kapwa, loób. In other words, I return to my center. I write from there” (Wanna, p. 107). The words loób and kapwa, which themselves appear several times in Letters, speak to Filipino conceptions of interiority and interconnectedness, respectively (pp. 61, 62, 63, 64, 60, 61, 65). In Wanna, Reyes associates these values with the letter and mixtape forms: “Aren’t these [forms] the places we come to understand how we are connected to one another—kapwa. Aren’t these the places where soul-bearing necessarily happens—loób” (p. 108). Thus, the epistolary use of you expresses those deeper, spiritual visions that are represented by letters and letter writing: connections with others, soul bearing, soul sharing. It is with a sense of our mutually constitutive interconnections that Reyes writes to you, about you, and as you.

After “Brown Girl Fields Many Questions” defines you and several other terms, the poem turns to the questions in question, a long list of mucky, gritty punches in the gut, most of which start with “what’s it like when . . .,” then describe painful experiences. One example: “what’s it like to have white people coming up so close, gawking and poking at your flat little nose, your little body, touching your silky hair” (Letters, p. 9). Another: “what’s it like when they say your boys are hoodlums and your sisters are indecent, all your girls are whores, just go back to where you came from, go back to where you came from, go back because you don’t belong here, because we never wanted you in our neighborhood” (p. 11). Follow the pronouns. These questions are something that “you” ask, per a comment earlier in the poem, “Here are some questions you might consider” (p. 9, emphasis added). But these questions also describe things that happen to you, per the repetition of “your . . . your . . . your . . . your . . . your . . . your” and “you . . . you . . . you” in these two questions alone (9, 11, emphasis added). The implication is that the expansive you is stuck in this shit as both asker and askee. “You” are asking this, about yourself, “your” boys, “your” girls. “They” may be the ones saying these awful things, but, per Reyes’s definition, even “they” may be included in the “you,” too. So the poetics of you are not separable from the poetics of fuck: fuck you and you’re fucked, too.

But you sing, too. The poetics of you are also not separable from the poetics of sing. Indeed, the questions do start as shit but then they shift. In Reyes’s book, being a young brown girl is far from all and only negative. One of the final questions in the poem illustrates this shift: “how are you still here breathing, working, bustling like a motherfucker” (p. 11). This question begins not with what is it like but with how, coming across less as a question and more as a declaration of awe. You may be fucked. But you are still here. You are breathing. You are working. You are bustling—which, as Urban Dictionary explains, means operating at “an unusually high degree of intensity.” While this hard first poem of the book refuses to retreat into false triumph, it nonetheless meets the brutal facts of racism, sexism, capitalism with the brute force of survival, of hustle, of presence, of persistence. You have Reyes singing your praises, in songs as multifaceted and even contradictory as “you” are. Letters is a book with a message. While so-called high literature may (pretend to) eschew such messages (Keats’s “palpable designs”), low literature gets to have something to say, gets to say it directly. The message of Letters does not outweigh its aesthetic and formal poetic choices because it is one of its aesthetic and formal poetic choices. The message, indexed through the book’s three key words, is that “you” will have to reject the definitions, demands, and discriminations of others and exert your own agency. But this isn’t a message of individualism because “you” exist in context, community, contradictory connection with countless others, even including those who would do you harm (“you” harming “yourself”). “In this fast and gritty place,” Reyes writes of herself and, especially, other Pinay writers, “we are creating spaces for us to congregate, to explore and hone our craft, to amplify. We are defining our own literary and artistic traditions. We are not asking for anyone’s permission” (Wanna, p. 151). In the muck, “you” (“we”) can sing, have to sing, are already singing.