Coyote Shook is a cartoonist, PhD candidate, and medieval mystic derailed by circumstance. Their writing and comics have appeared or are forthcoming in a range of Canadian and American literary magazines, including Tupelo Quarterly Review, LandLocked, Vox, The Portland Review, The Michigan Quarterly Review, The Puritan, Shenandoah, and various others. For more on their work, visit their website, coyoteshookcomics.com or their Instagram, @coyoteshook

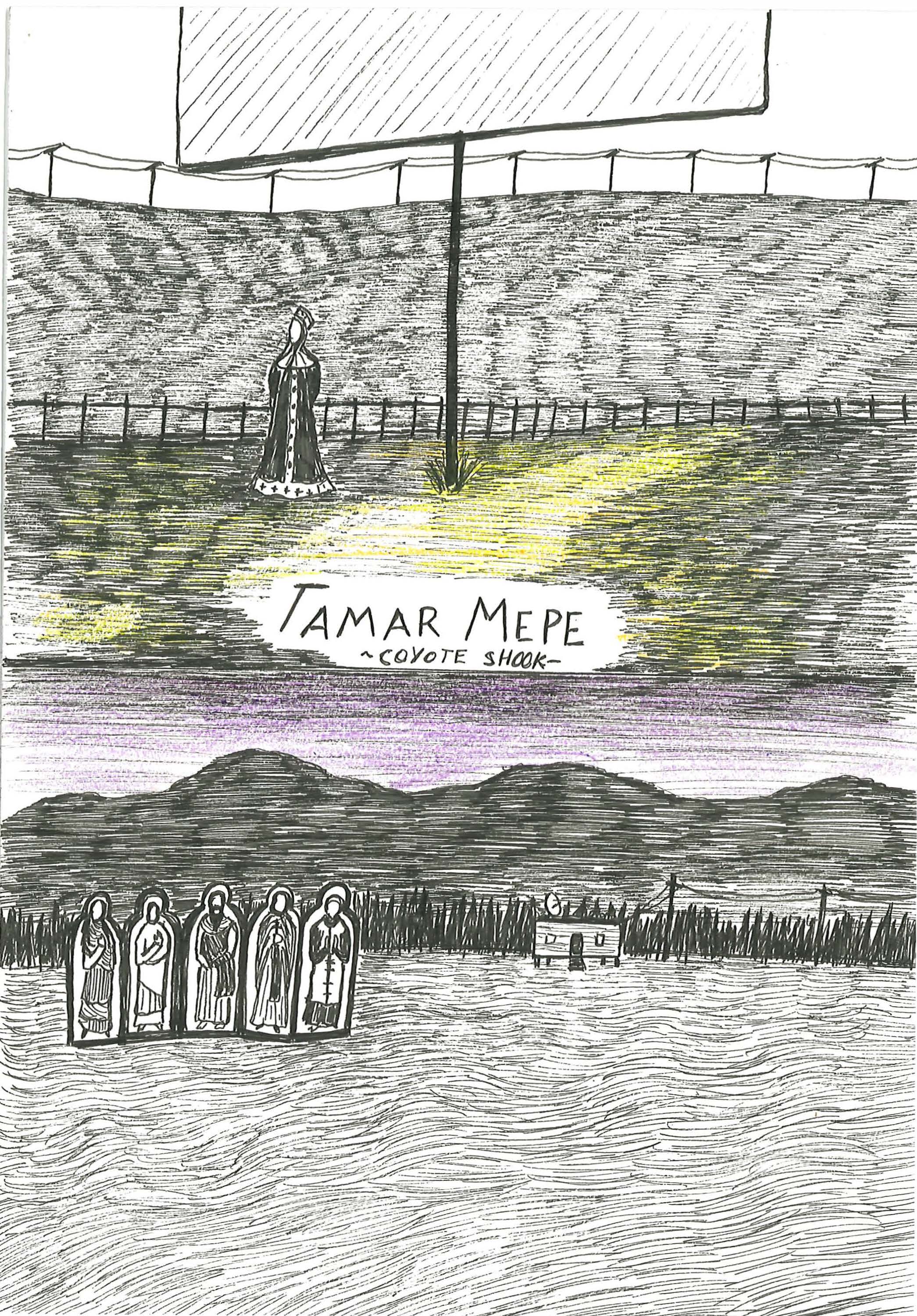

Our art editor, Leslie Vega, asked Coyote a couple of questions about their captivating Tamar Mepe, which we are thrilled to publish below:

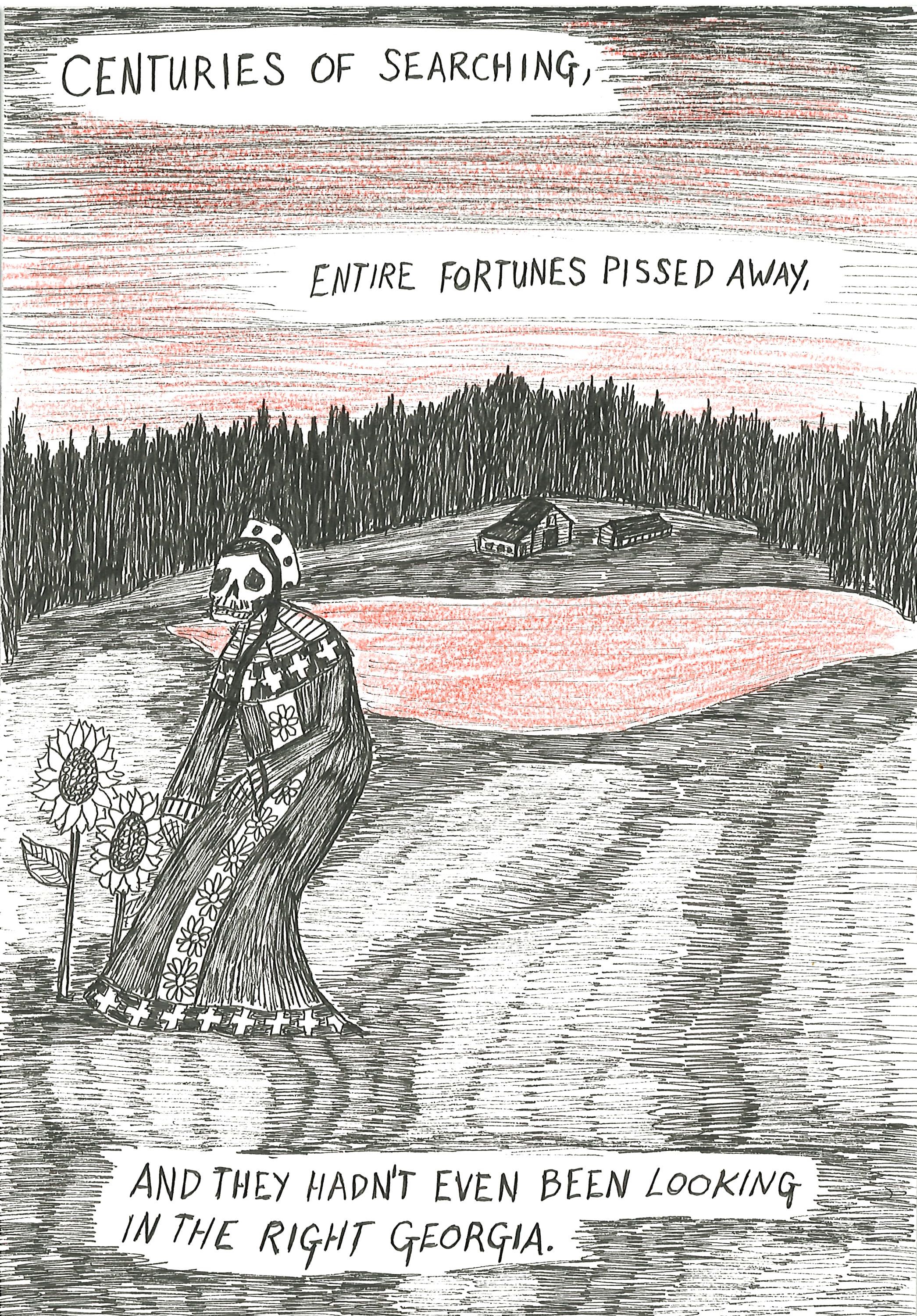

Vega: Tamar Mepe is a bleak, beautiful tale of two Georgias. How has the Appalachian South shaped your identity as an artist?

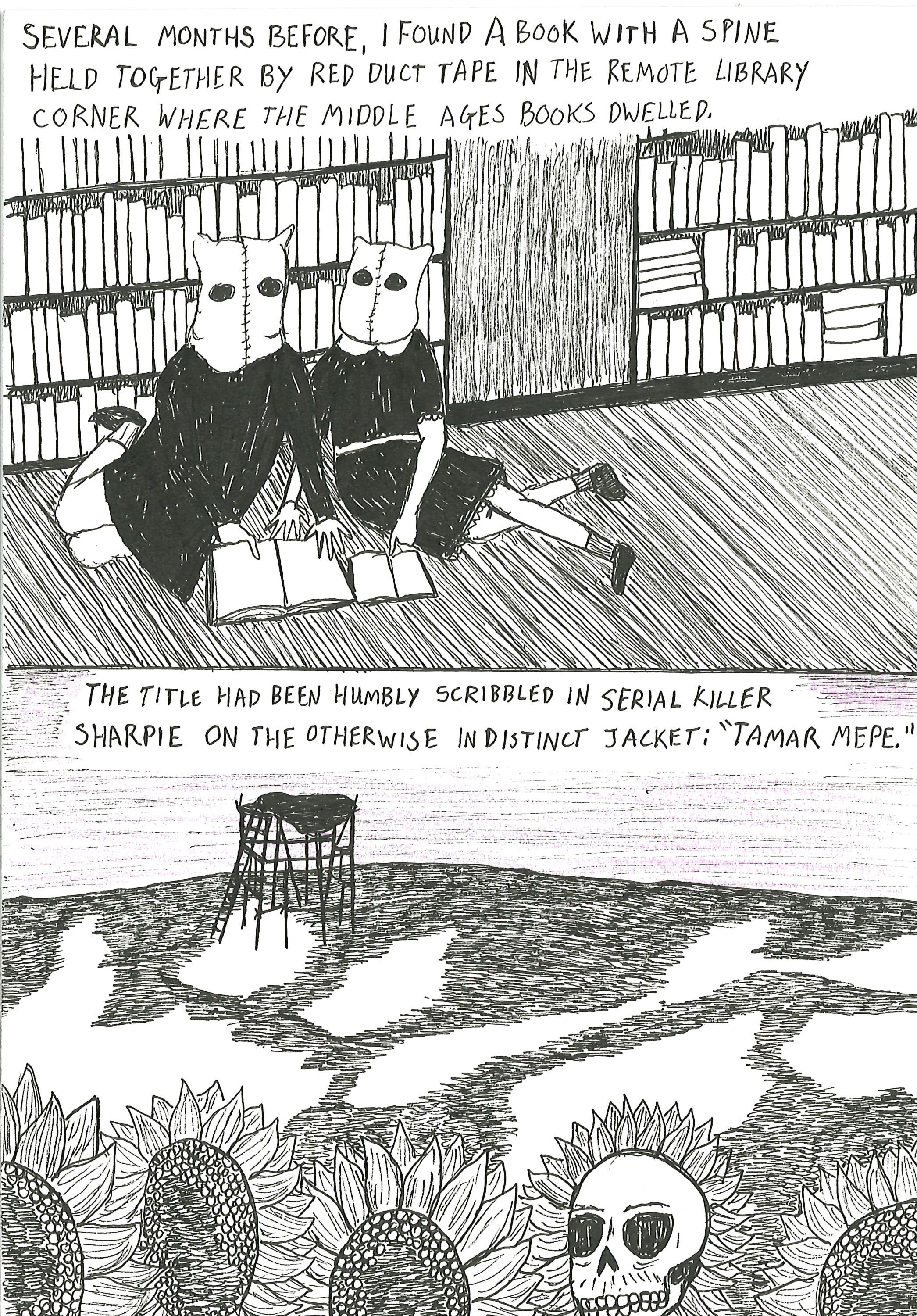

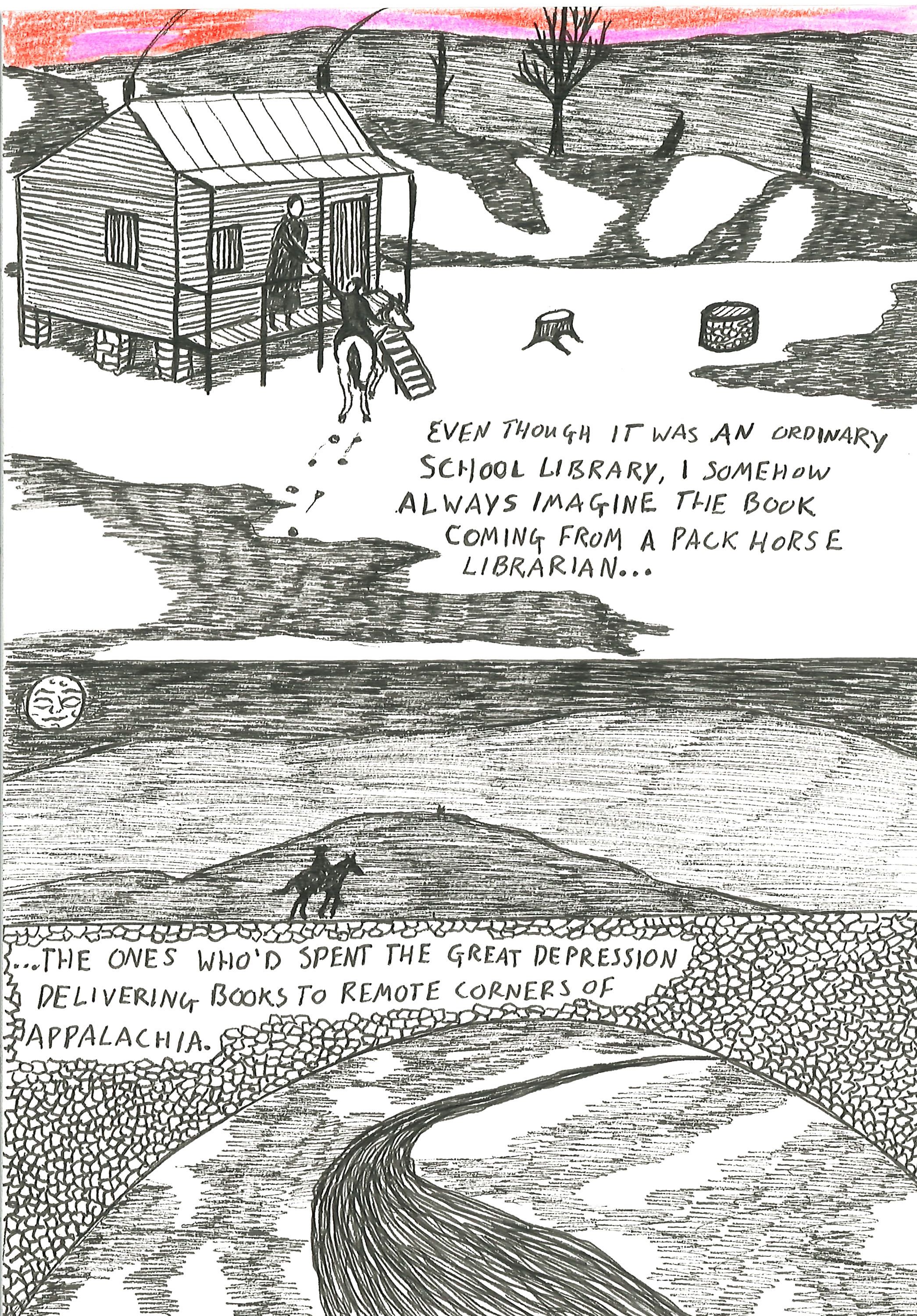

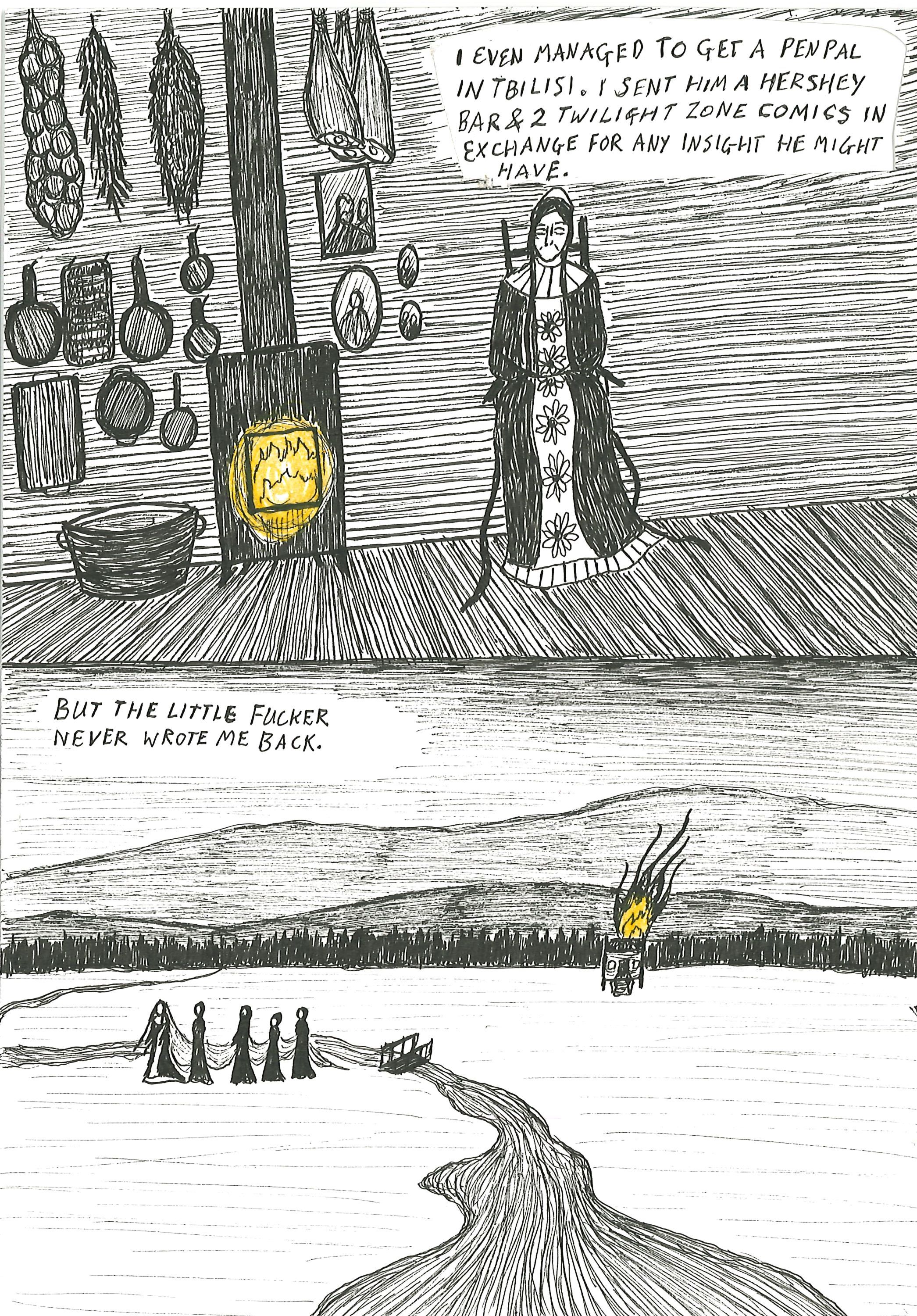

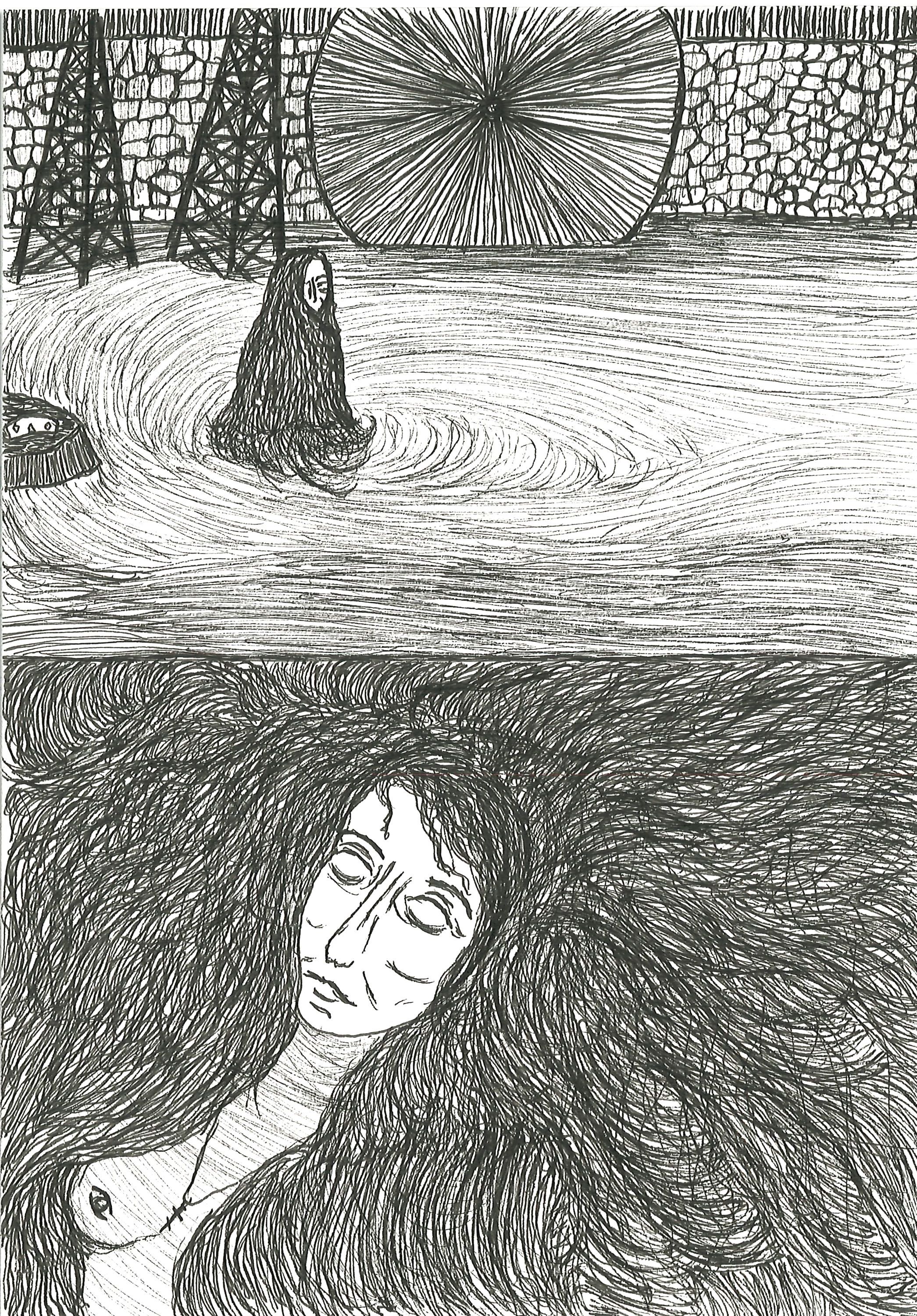

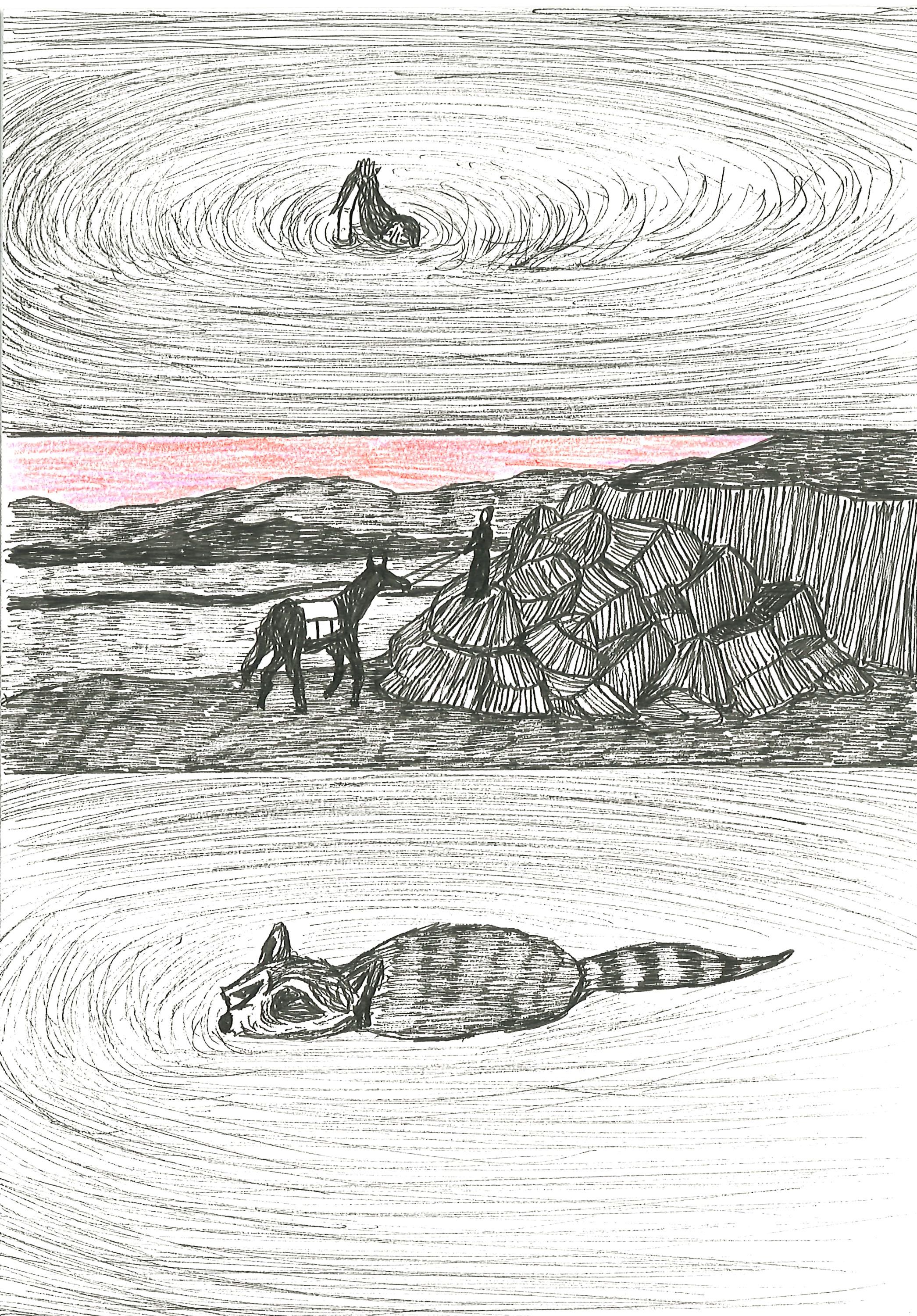

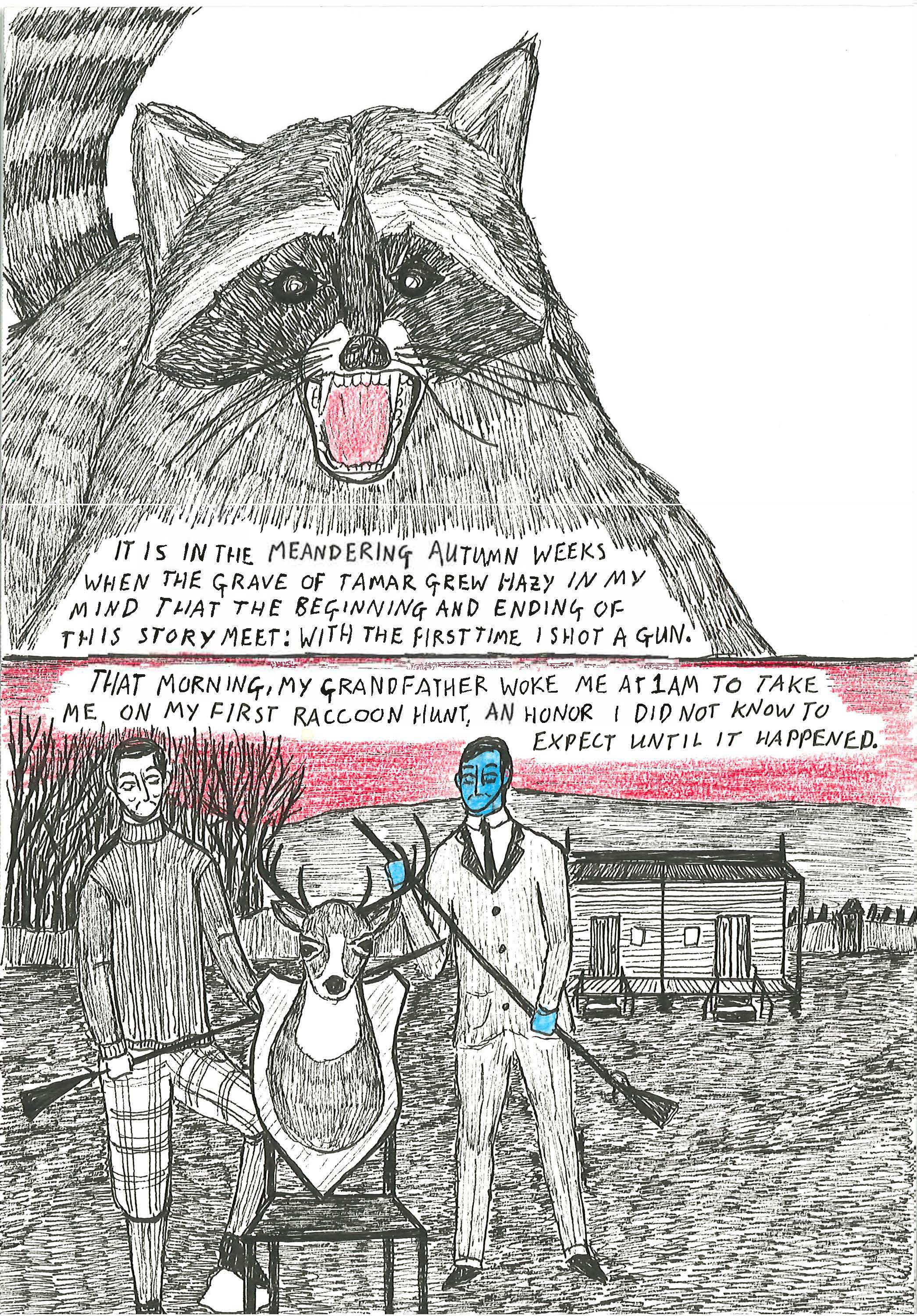

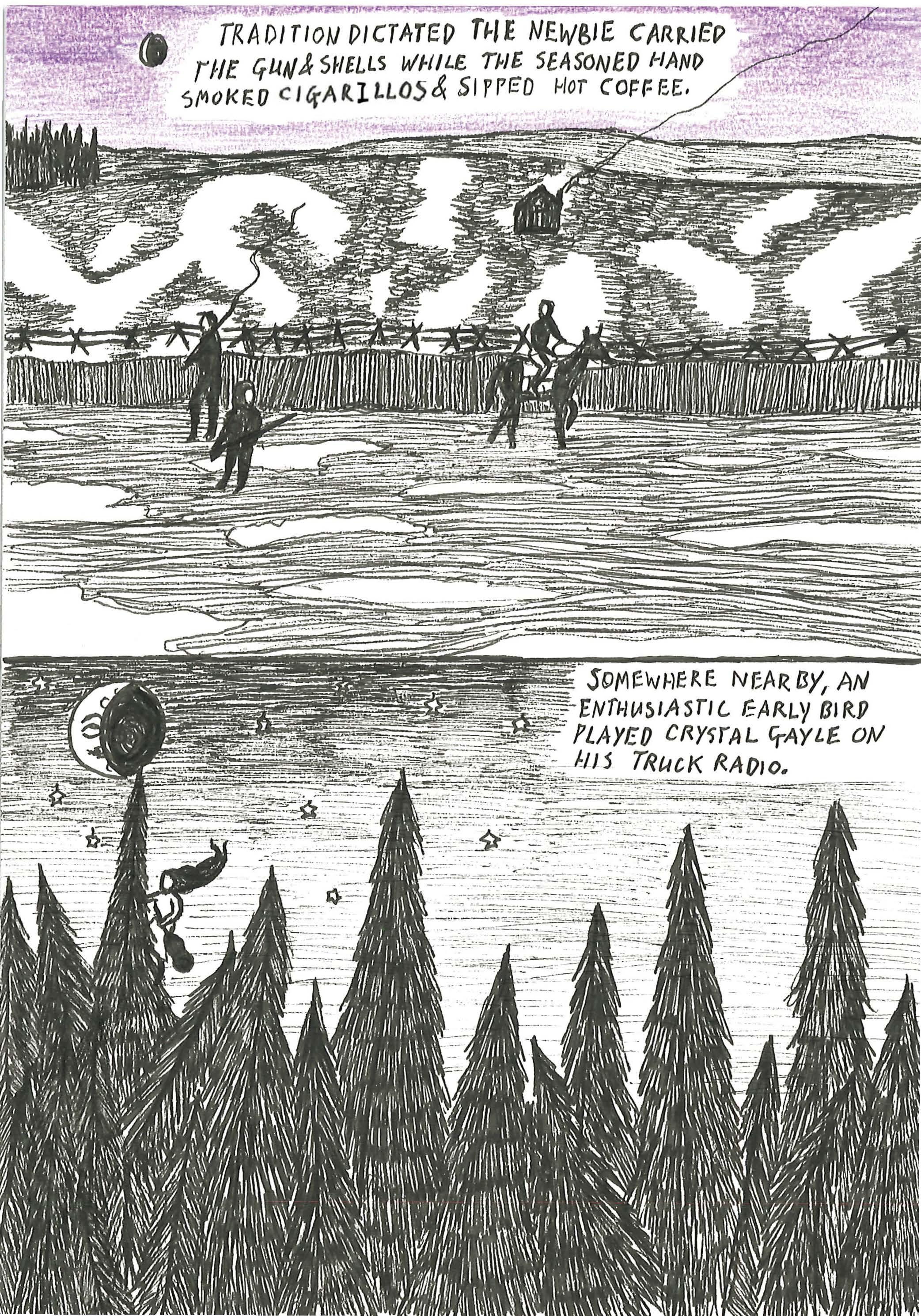

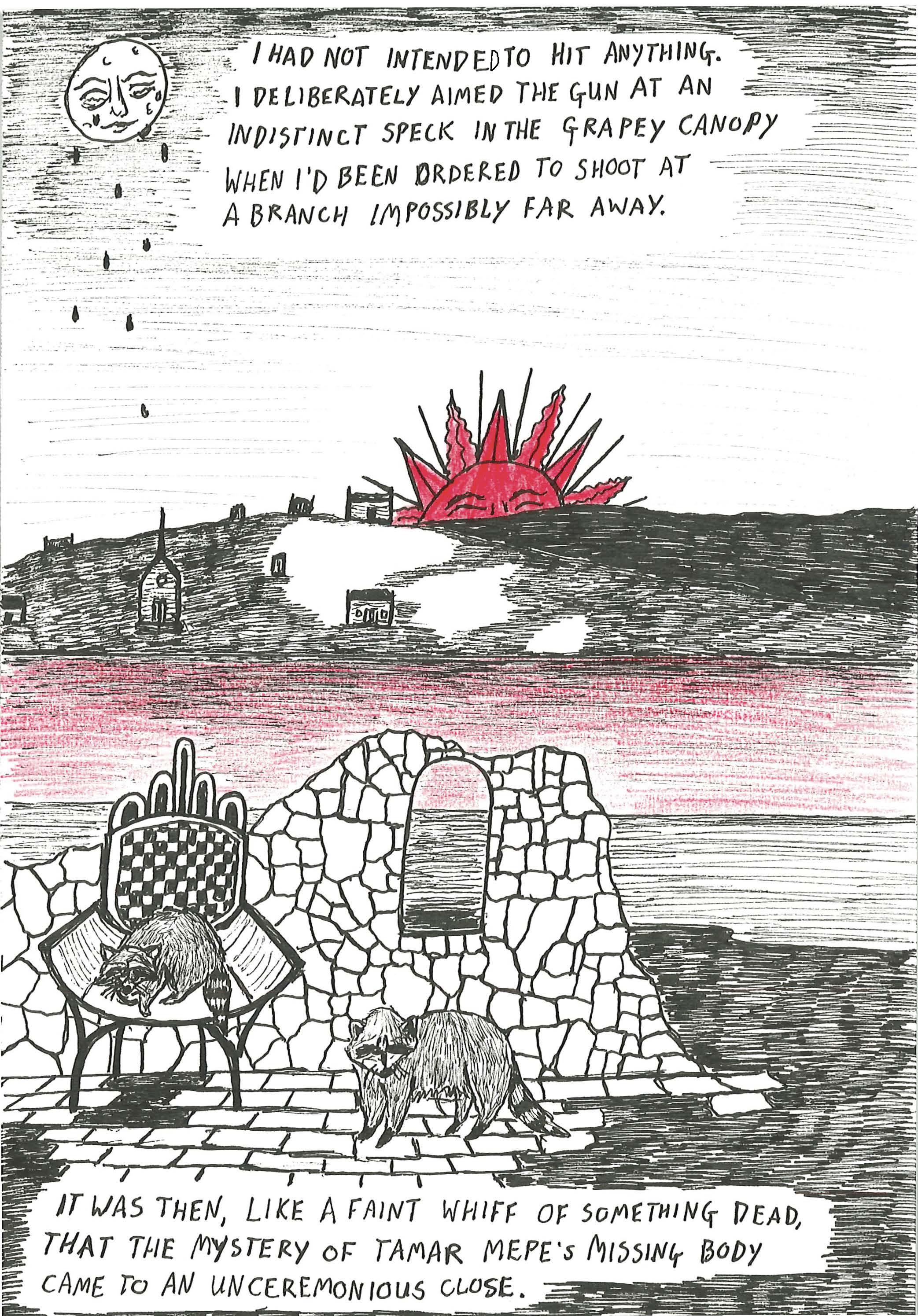

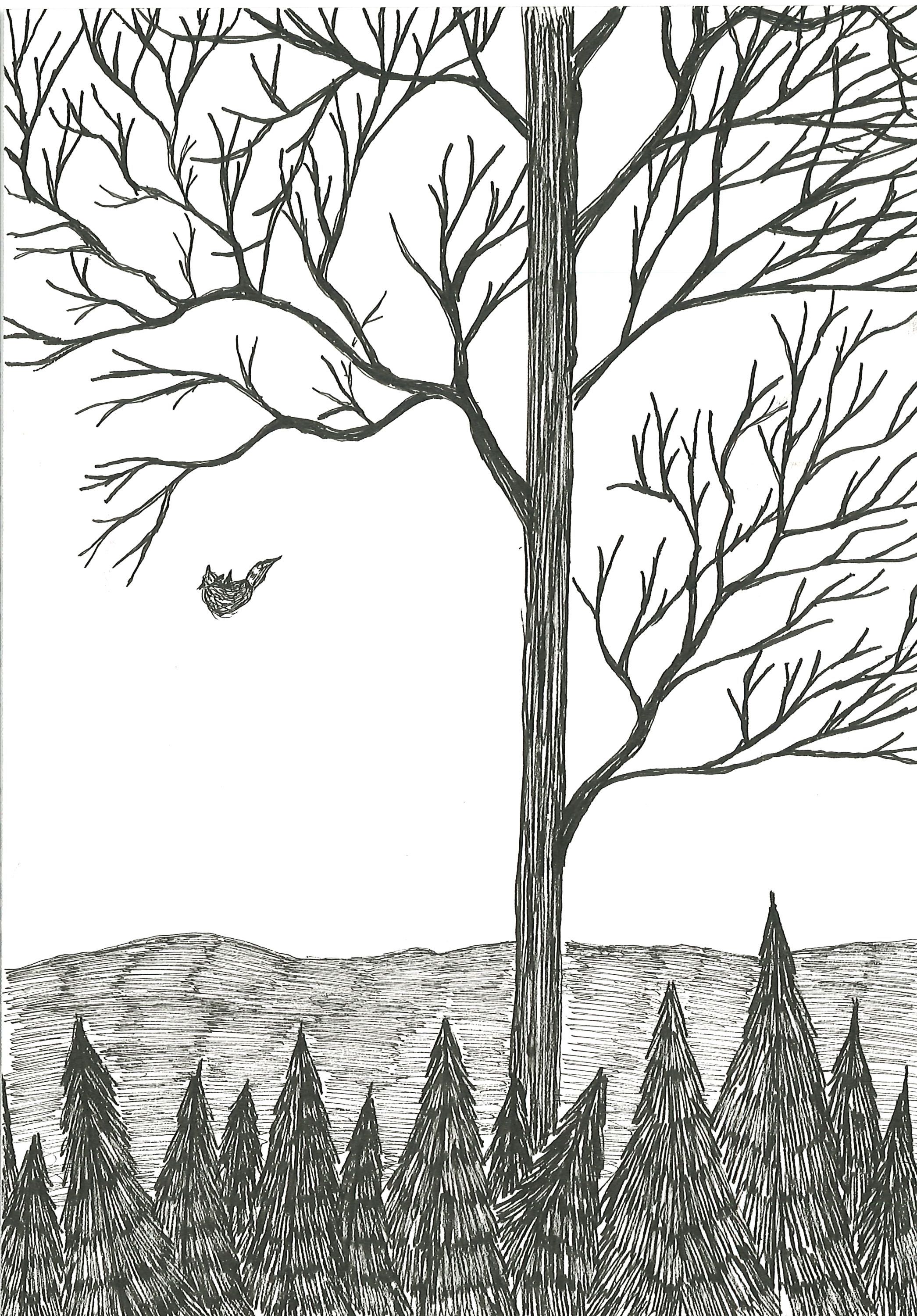

Shook: I love this question, and I am in the process of working on a paper about why Appalachian culture lends itself so beautifully to comics-as-story-telling. I think that growing up in an area that is so misunderstood, centering individual experiences that look from the inside outwards tends to do the work of social justice-through-story-telling that is so crucial to Appalachian studies. Partly, growing up in Appalachian Georgia was a remarkably visual experience. There are many visuals from my memories there (quilts, canning supplies, abandoned distilleries, raccoon pelts, etc.) that stick out in my mind when I think about what stories I want to tell and how I wish to tell them.

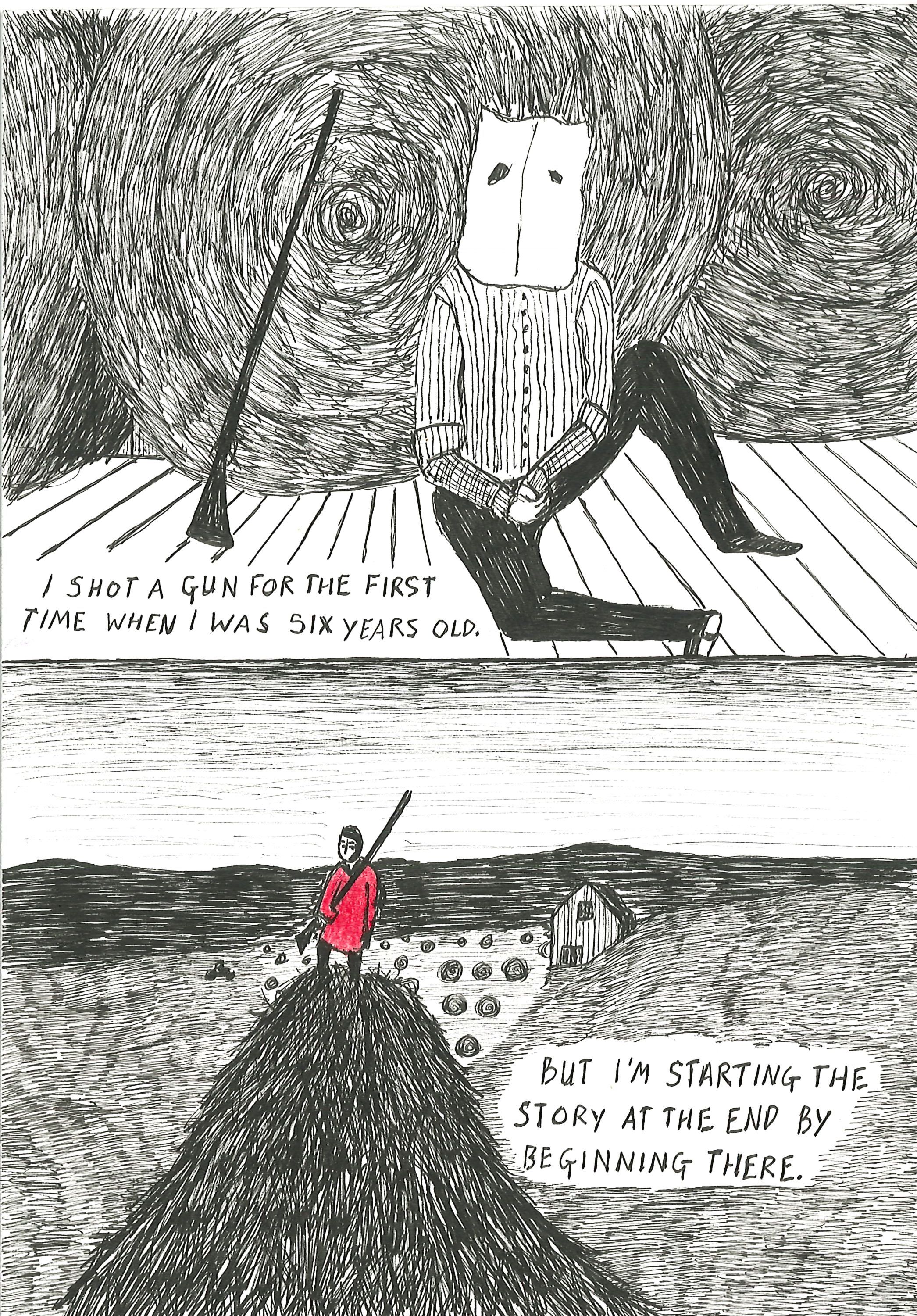

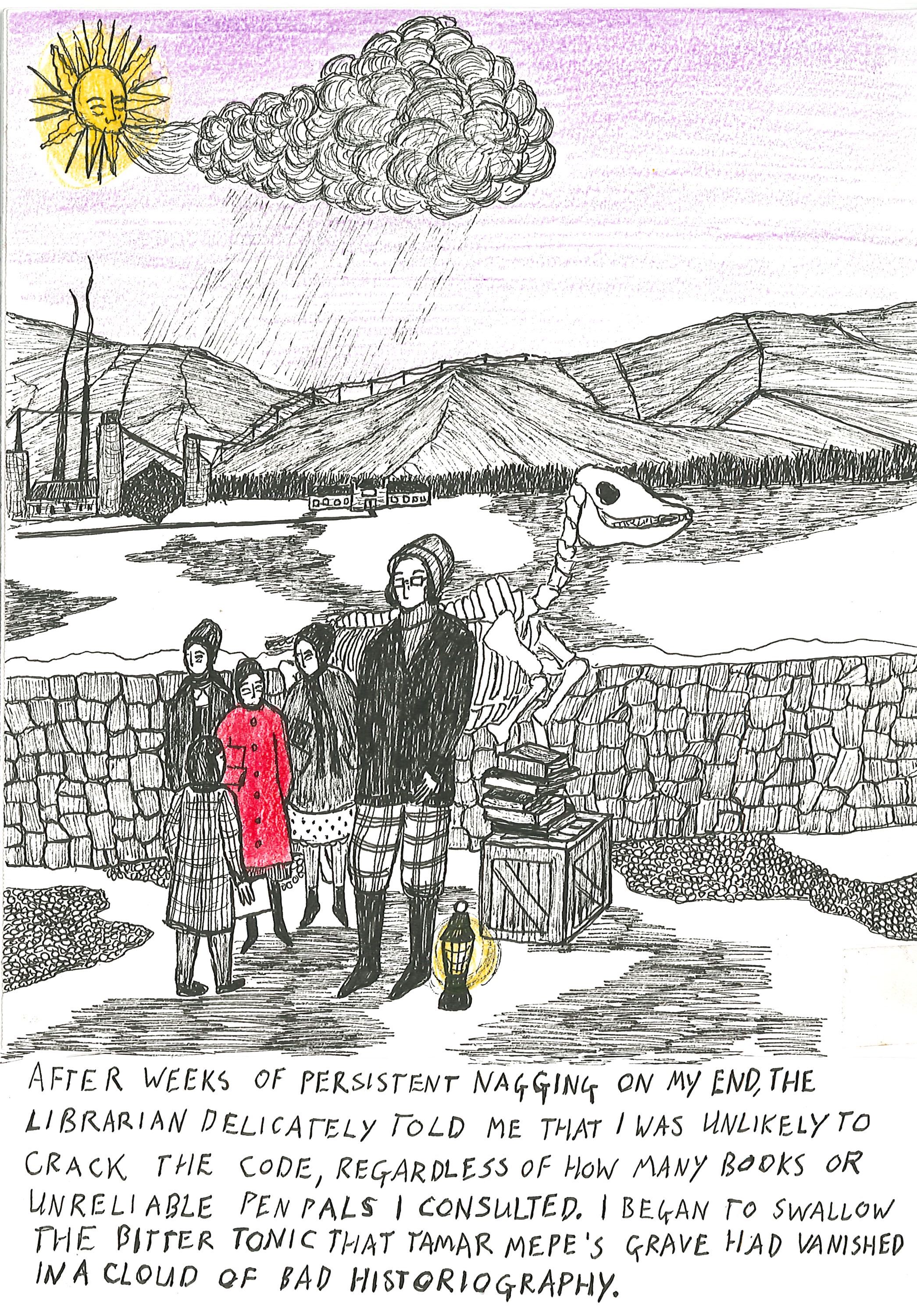

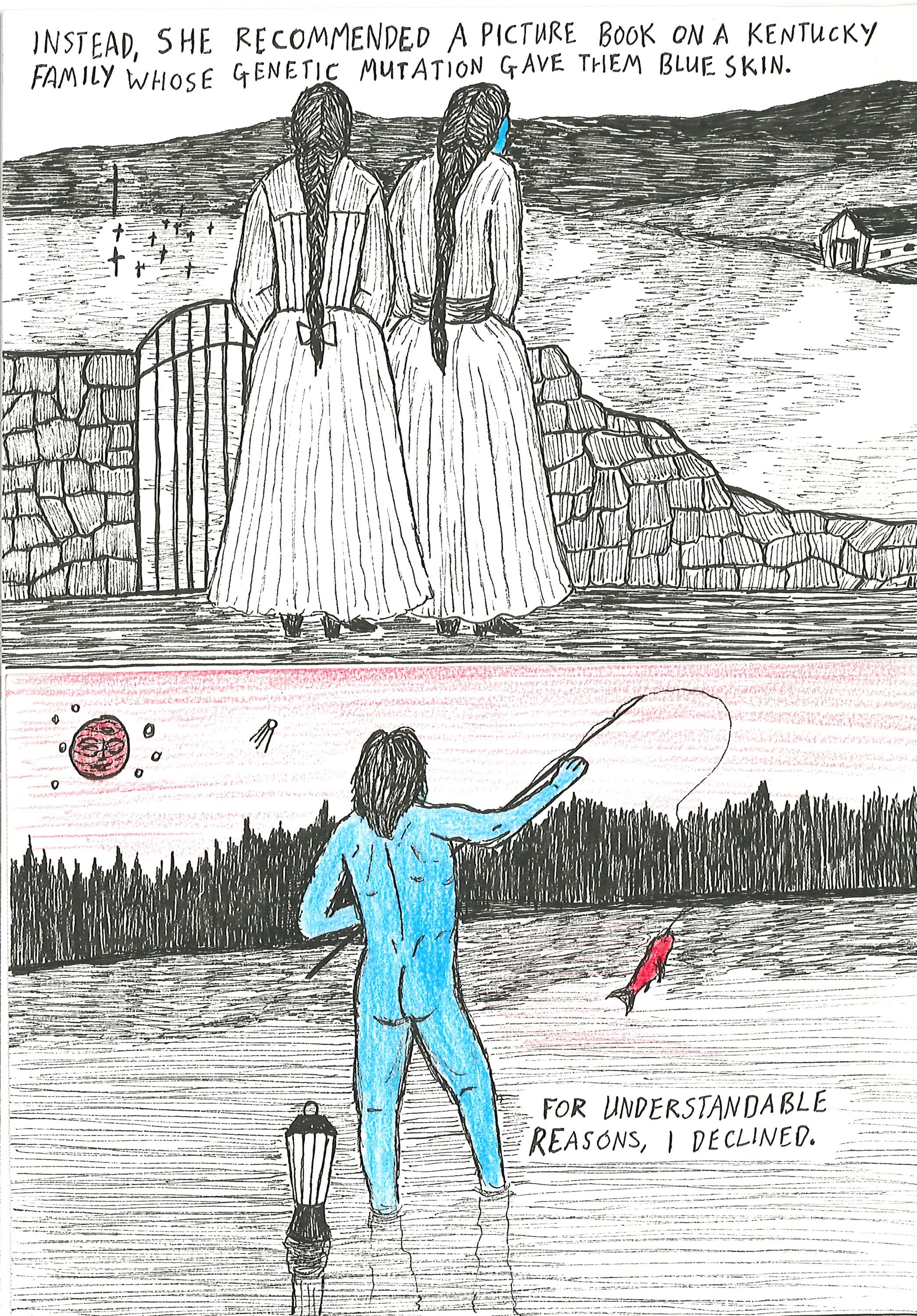

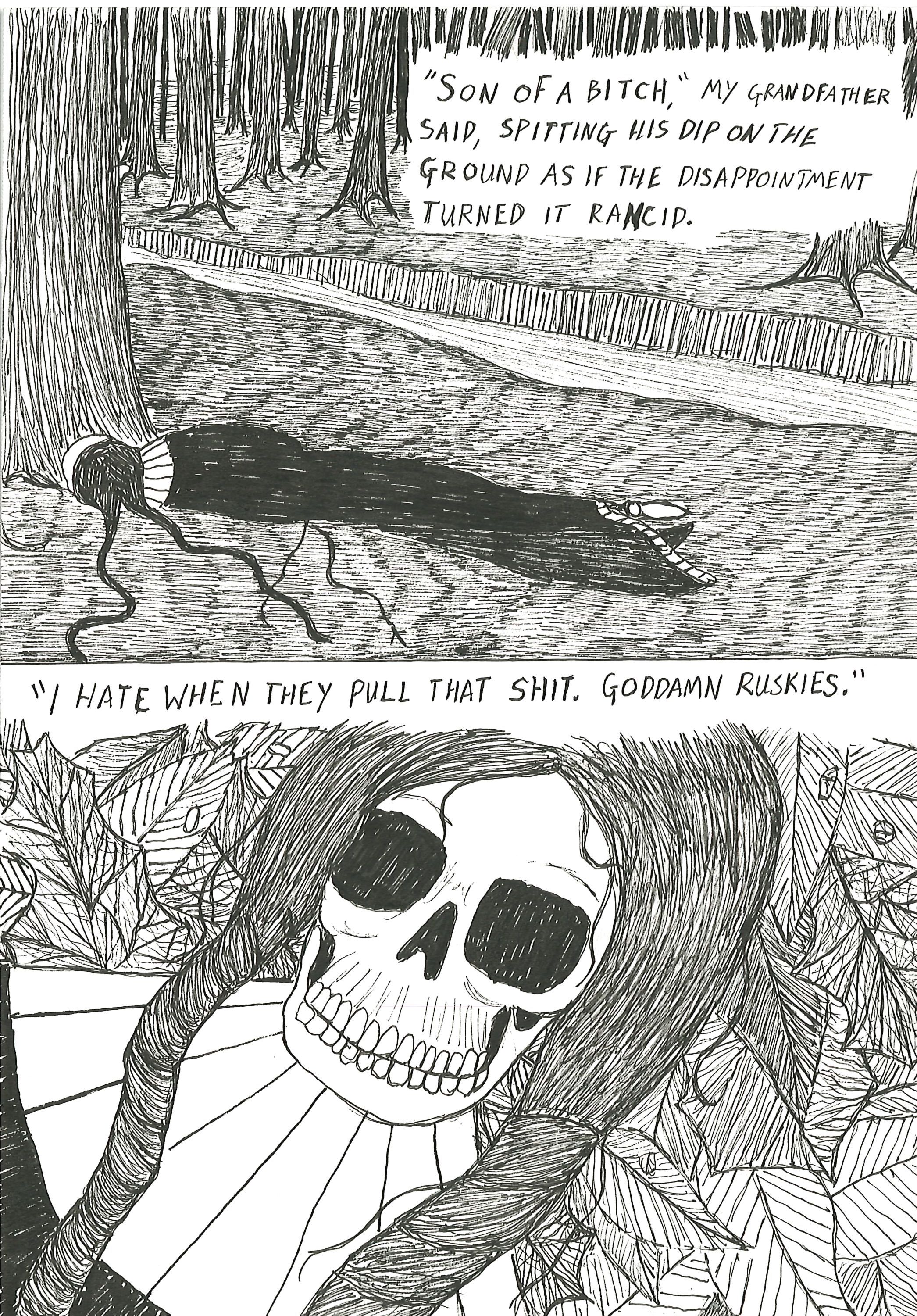

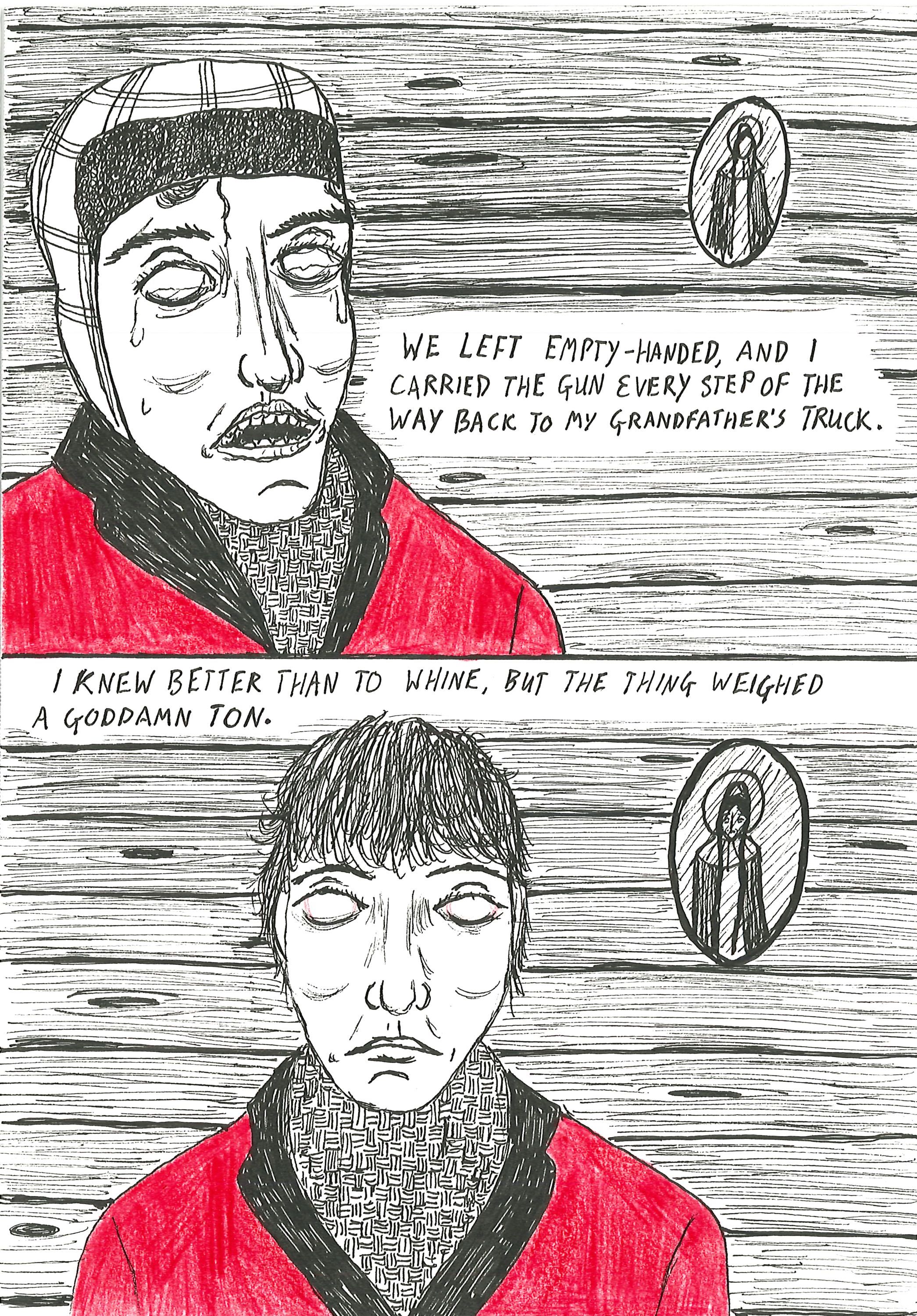

I struggle with being from Appalachia and trying to communicate that in my writing, but perhaps not in the way I might have once thought. I think people of all stripes tend to mythologize and homogenize a region of the US that is as big as California. I also think that part of my journey as a writer and artist has been influenced by authors like NK Jemisin about the need to break those myths by de-romanticizing the rural space as innately idyllic and wholesome, something that applies to both my background in Appalachia and my approach to medieval studies. I did not want to create an idealized Appalachia that glosses over the harsh aspects of living in that place, nor did I want to present an easy list of cliches that the region is backwards and innately hateful. My experiences would be out-of-place with such reductive conclusions. My childhood, as did many childhoods, had beautiful and bleak moments that existed simultaneously. It was not a jolly-holiday of socialist, striking coalminers and Dolly Parton music, as many a paternalistic people not from the region might insist. Nor was it some sort of wholesome dip into small-town Americana that gives people the chance to bask in small-government ruralism (like a right-wing relation through marriage of mine who lives in a suburb shops exclusively at Whole Foods recently said). Disturbing things and lovely things could happen. That is the sort of earthy, sometimes acrid hummus I want to dig into in my work as an Appalachian cartoonist.

I draw a significant amount of inspiration from the work that places like Foxfire, John C. Campbell, and the Highlander Center do in terms of a fusion of folk-knowledge and wisdom and a dedication to progressive action in the region. I am still working on how to fuse my methods of folklore studies and forward-facing story-telling, but reading my long-dead great-grandpa’s Foxfire books really helped in that regard. There are stories, for example, about snakelore, about how to tend to a dead body in areas where there is no access to embalming fluid, ghost stories, and individual tales of elderly people picking blackberries to sell to afford a trip to the eye doctor. Those sorts of anecdotes interest me greatly.

Vega: Describe your process. Does the writing come first, or is the story unveiled more like a series of film stills?

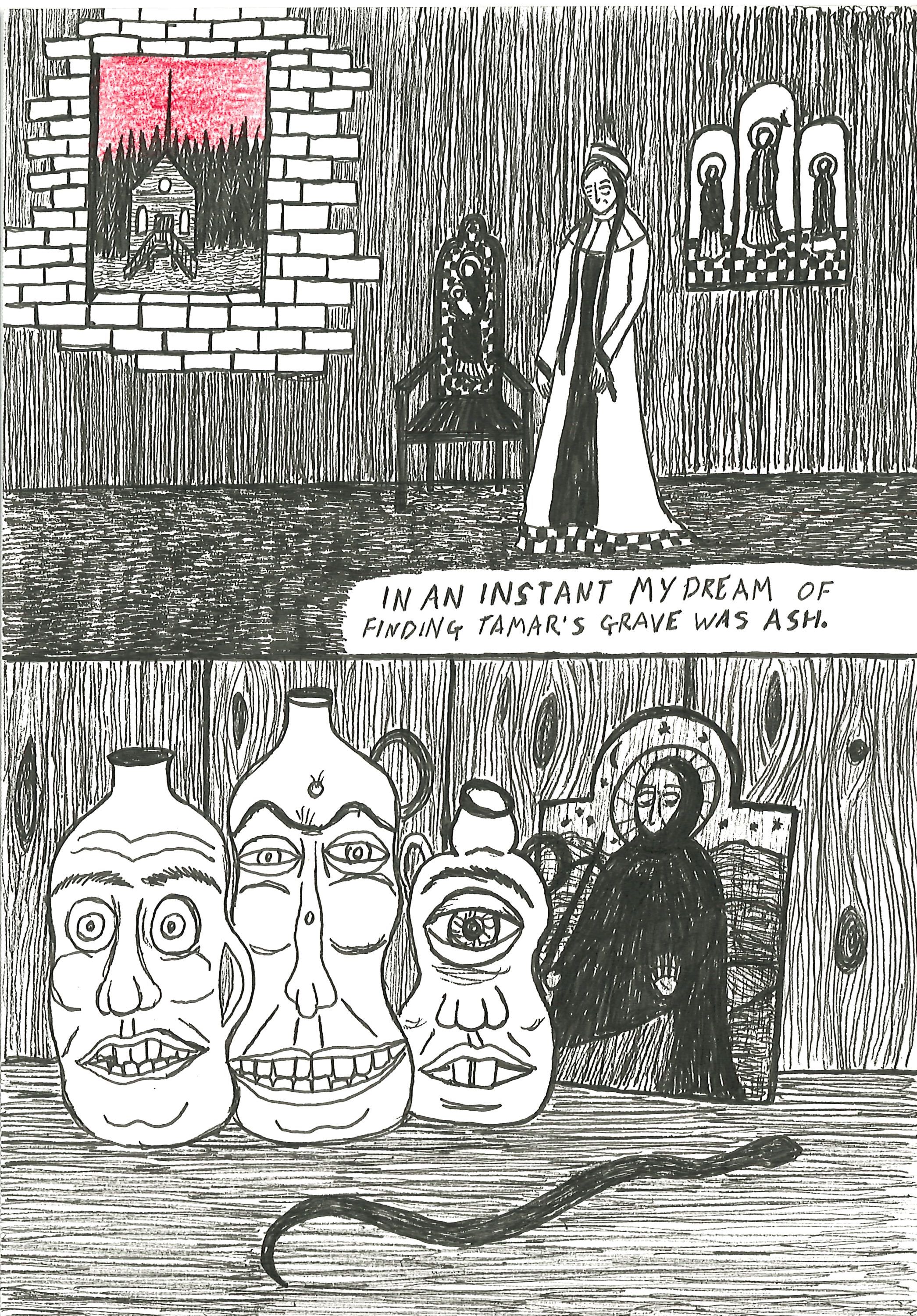

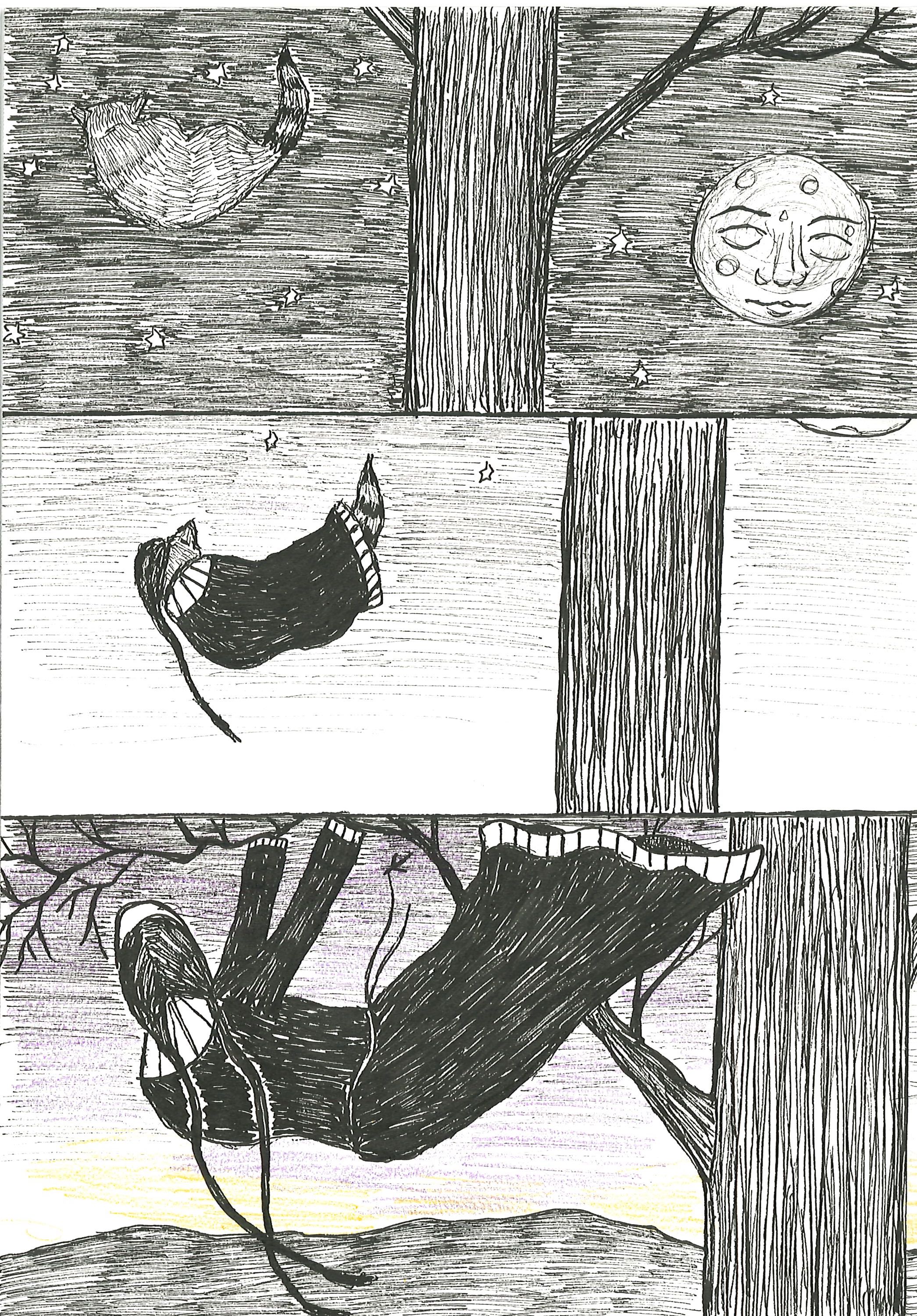

Shook: This varies depending on the piece. Tamar Mepe was a VERY visual piece for me. I knew how I wanted the piece to end (because it begins with the ending). A lot of this was looking at pictures of abandoned churches in coal country and in Georgia’s and North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains while also looking at photos of monastic ruins in Georgia and original artwork of Queen Tamar. The innards and guts of the story came later, in this case. Other times, when a story is more word or plot driven, the drawings tend to respond to the words. Sometimes, I like to make a deliberate disconnect between words and images when I think it might be constructive to do so.

Vega: Comics are a popular contemporary platform for autobiographical narrative. What makes this particular form of storytelling so evocative for you?

Shook: Plasticity and the boundaries of narration being flexible. I love the idea of an autobiography told through folk-comics. Many of us are unreliable narrators when it comes to our own lives. Memory and perception are not trustworthy, and, as a queer writer, I get irritated and disheartened by the over-saturation of queer comics that feel they must a) be completely truthful and accurate stories and b) evoke empathy from cisgender and heterosexual readers. I think queer cartooning and folk cartooning are well-positioned as forms to allow for a universe where the grim, the magical, and the fantastical exist side-by-side. I might tell an accurate story (such as the time I accidentally attended a Pentecostal mountain church service on a classmate’s invitation), but pair the “truthful” aspects of the story with magical-realist and disturbing folk imagery. It stretches the boundaries of category and does really fascinating work in the “speculative nonfiction” category. It is interested in truth, but less so in accuracy. Is folklore truth or fiction? Do those distinctions even matter? What truth comes out of meditation? What observations or sharp moments stick out from a blending of memory and a desire to remember how something ought to have been as opposed to how it was? I think cartooning is evocative for me because I like the desire to lean into my own unreliability as a narrator and, by doing so, subvert expectations that queer people and queer cartoonists “owe” accurate (and usually tragic) narratives about persecution and coming out to readers. I believe that queer story telling can and should be risky and challenging, and, ideally, disrupt and disturb the status quo rather than soothe it.

Follow us on twitter @TampaReview and on instagram @tampa_review

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.