Patricia Hooper is the author of five books of poetry, Other Lives, At the Corner of the Eye, Aristotle’s Garden, Separate Flights, and Wild Persistence, the last two published by the University of Tampa Press. Her poems have appeared in many magazines, including The Atlantic Monthly, The American Scholar, Poetry, The Hudson Review, The Gettysburg Review, Southern Review, The Yale Review and The Kenyon Review. A graduate of the University of Michigan, where she earned B.A. and M.A. degrees and was awarded five Hopwood Awards, she has been the recipient of the Norma Farber First Book Award, the Bluestem Award for Poetry, a Writer’s Community Residency Award from the Writer’s Voice, the Laurence Goldstein Award for Poetry from Michigan Quarterly Review, The Anita Claire Scharf Award from the University of Tampa Press, The Roanoke-Chowan Award for Poetry from the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association, and, just announced this month (July 2020), the 2020 Brockman-Campbell Award from the North Carolina Poetry Society for the best book of poetry by a North Carolina writer. She lives in Gastonia, North Carolina, where Tampa Review Editor Richard Mathews asked her to reflect on the natural beauty around her and the idea of “persistence” in light of the global pandemic.

Patricia Hooper is the author of five books of poetry, Other Lives, At the Corner of the Eye, Aristotle’s Garden, Separate Flights, and Wild Persistence, the last two published by the University of Tampa Press. Her poems have appeared in many magazines, including The Atlantic Monthly, The American Scholar, Poetry, The Hudson Review, The Gettysburg Review, Southern Review, The Yale Review and The Kenyon Review. A graduate of the University of Michigan, where she earned B.A. and M.A. degrees and was awarded five Hopwood Awards, she has been the recipient of the Norma Farber First Book Award, the Bluestem Award for Poetry, a Writer’s Community Residency Award from the Writer’s Voice, the Laurence Goldstein Award for Poetry from Michigan Quarterly Review, The Anita Claire Scharf Award from the University of Tampa Press, The Roanoke-Chowan Award for Poetry from the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association, and, just announced this month (July 2020), the 2020 Brockman-Campbell Award from the North Carolina Poetry Society for the best book of poetry by a North Carolina writer. She lives in Gastonia, North Carolina, where Tampa Review Editor Richard Mathews asked her to reflect on the natural beauty around her and the idea of “persistence” in light of the global pandemic.

=========================================================================================

Richard Mathews: Congratulations on the recent news that the North Carolina Poetry Society has honored you for Wild Persistence by awarding your book the 2020 Brockman-Campbell Award as the best book of poetry by a North Carolina writer published in the previous year. This puts you in very good company. Previous winners include Shelby Stephenson, Fred Chappell, R. T. Smith, Betty Adcock, Dannye Romine Powell, and a host of other wonderful writers.

What are some of the ways you think of yourself as a “North Carolina writer”? Do you think this book in particular has ties to North Carolina as a place?

Patricia Hooper: Thank you, Richard. The truth is, I really don’t think of myself as a North Carolina writer, even though Wild Persistence is influenced by the landscape of this beautiful state. I lived in Michigan all my life, and when we moved here in 2006, I was so homesick that I searched the weather channel for reports of snow storms just to relive what they felt like. Some of the poems in Wild Persistence—“Moving South” and “End of Summer in the Piedmont,” for example—have to do with that displacement. Many take place in Gastonia, where I live, or nearby in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Before we came here, I already loved the literature of the South, but it has such a rich, regional heritage that an outsider can never appropriate it. Reading Thomas Wolfe or Reynolds Price or Lee Smith, you realize that you have to have deep roots in the South in order to be truly of it. Even so, North Carolina is now a significant part of my experience, and I’m grateful to have this book recognized in my new home state.

Mathews: I have always loved the title of this collection. It is a bit of an oxymoron—that is, “wild” suggests something almost frantic and untamed, while “persistence” suggests patience, planning, and civilized focus. One is a short, four-letter word; the other is a fancier, multi-syllable, thirteen-letter word. On the other hand, nature in the wild does itself have persistence—the kind of persistence that can allow plants and trees to sprout and grow out of cracks in the pavement. How did you come up with the title?

Hooper: When I was assembling this collection I noticed many poems that focused on the idea of nature’s persistence—the ones about the mockingbird, who learns so many songs and sings so earnestly, the final poem, “Ode,” which praises the perseverance of trees, and several others about nature’s relentless cycles, poems in which plants and birds die and go back to the earth, fueling its renewal. At the same time, I was thinking about the capacity in human beings to survive adversity, often through fierce determination and grit. And I was also thinking of what seems an almost pre-rational necessity in the poet to find language for experience, something that requires obsessive patience and perseverance if it’s going to transform itself into art.

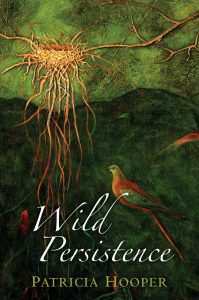

Mathews: The cover of this book—like your previous book from the University of Tampa Press, Separate Flights—features a painting by the artist Suzanne Stryk, this one from a piece entitled “Homage to the Passenger Pigeon (extinct 1914).” Are there particular aspects of her work that resonate for you? Was there special appeal in this homage to an extinct bird?

Mathews: The cover of this book—like your previous book from the University of Tampa Press, Separate Flights—features a painting by the artist Suzanne Stryk, this one from a piece entitled “Homage to the Passenger Pigeon (extinct 1914).” Are there particular aspects of her work that resonate for you? Was there special appeal in this homage to an extinct bird?

Hooper: I find Suzanne Stryk’s work amazing! She’s a naturalist, and she pays close attention to the details of the natural world: the structure of a bird’s wing, the bodies of insects, the woven patterns of nests. And then she uses these meticulously rendered images to create paintings that have strong emotional content, reimagining and arranging them in such unusual ways that they move into the realm of the surreal. In the cover painting, “Homage to the Passenger Pigeon (extinct, 1914,)” the passenger pigeon sits in the foreground apart from a nest. The nest, which seems to be floating precariously on the branch above it, is alive with light and motion in contrast to the pigeon’s eerie stillness. There are no extinct birds in this book, but there are reminders that life is fragile and can disappear at any moment. Nature perpetuates itself, as we do, but for how long?

Mathews: Your book was not written or published in the context of a pandemic, but we are all now reading and thinking differently in the midst of fighting Covid-19, and I have found the title and many of the poems taking on new relevance in light of the persistence demanded of us in this fight. Are there any poems in the book that seem particularly relevant or meaningful to you in this new context?

Hooper: I certainly wasn’t thinking about the possibility of a pandemic when I wrote these poems. But it pleases me that they spoke to you in a new context. For me, those that relate most to what we are going through are those that have to do with how normal life can change in an instant, the ones about a debilitating accident, a missing child, an unexpected death, or a terrorist attack. And it may be those that have to do, simply, with resilience. People are thrown back, just now, on their own resources, and many are spending more time outdoors—walking, gardening, and even sitting in their front yards—not only to feel less isolated but to enjoy the relative normalcy of the natural world. Daily life is radically different, but even though nature doesn’t always act in our best interests, it still has the power to heal and console.

Mathews: Well, in Wild Persistence I think you have connected with that power in ways that bring the forces of language and literature together with those in the natural world to magnify and reinforce the healing and the consolation. Both North Carolina and Michigan—as well as those of us based elsewhere—can rejoice and be heartened by that.

=========================================================================================

Wild Persistence is available from the University of Tampa Press, along with Patty’s other UT Press title, Separate Flights.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.