Thomas Heise earned his PhD in English from New York University, where he specialized in twentieth and twenty-first-century American literature and culture. He is the author of three books in three different genres.

His first book, Horror Vacui: Poems (Sarabande, 2006), explores the relationship between writing and emptiness, loss, blank space, and difficult memories. Its title comes from a phrase that describes the psychological and aesthetic impetus behind a range of artistic practices (Medieval illuminated manuscripts, Islamic tilework, Victorian interiors) that share a sense of productive anxiety over vacuums, visual silences, or any manifestation of absence.

His second book, Urban Underworlds: A Geography of Twentieth-Century American Literature and Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2011), is a literary and social history of the depiction of “troubling” city spaces (“slums,” “ghettos,” and “vice zones”) in American literary narratives, urban-planning initiatives, sociological studies, and newspaper journalism from the 1890s to the 1990s, including close readings of works by Henry James, Djuna Barnes, Claude McKay, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, John Rechy, Thomas Pynchon, and Don DeLillo.

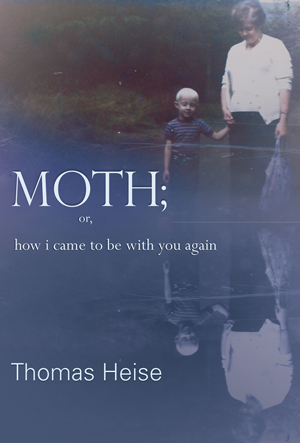

His third book and first novel, Moth; or how I came to be with you again (Sarabande, 2013), is a hybrid work that blends fiction, prose poetry, and memoir. It follows a narrator’s real and imagined journeys through time and space as he attempts to piece together a personal past he cannot remember and a present that is without direction. It was nominated for the ForeWord Book of the Year. The reviewer for Publisher’s Weekly wrote: “Heise seems capable of doing anything with words, and this book is a diagram of life’s ‘internal chambers’ that ventures into bleary territory hitherto thought unspeakable.” Novelist Carole Maso said, “It’s impossible to convey in a few lines the enormous pleasures of this book – the beauty of the design, the incandescent prose, its rigor and intelligence. A deeply melancholic and moving work of art.”

Heise says that what unites his writing is an aesthetic and intellectual preoccupation with the spatiality of human life, a deep, abiding interest in how personal and public places become encoded with sentiment, memory, history, ideology, and desire. He is currently finishing his second novel, Night Blooms, about people in New York, Berlin, and Naples, Italy, whose lives have been unsettled and turned increasingly dreamlike as a result of their inability to sleep for weeks at a time.

When Tampa Review Online decided to publish an excerpt from this novel-in-progress, editor Richard Mathews asked Heise to reflect the writing of the book, and on the process of extracting the piece he submitted, which we are pleased to publish below.

=======================================================================================

Mathews: Although we’ve published many short stories that went on to appear in short story collections in book form, we have seldom published excerpts from novels. To some extent, this is because most of the pieces from novels-in-progress that have come our way have tended to seem incomplete. They just didn’t seem to work well on their own. Of course, we don’t feel that way about this selection from Night Blooms. How did you go about finding a piece from your new book that you thought could become self-standing?

Heise: The structure of Night Blooms lends itself to excerpting, because it is organized around a series of stories told to the narrator, Michael, by his patients or by those whom he encounters through his research on sleep disorders, dreams, and nightmares. Some of these stories—of a haunted memoirist, an art historian obsessed with one of Matisse’s beautiful models, and a botanist who dreams of corpse flowers—extend across several chapters, but they are relatively self-contained. While these stories unfold, Michael’s own story of his thaw back into life after a divorce emerges across the book. Making some adjustments here and there, I excerpted a part of one of these stories out of the manuscript for Tampa Review Online.

Mathews: We noticed that you published quite a few excerpts from Moth in excellent journals before it appeared as a complete work. That must have given you some good practice in choosing what to submit. Can you mention any lessons about choosing things from a work-in-progress that you discovered during the writing of that book?

Heise: In some ways, publishing excerpts from Moth was easier. While Moth is a more fragmented and experimental narrative than Night Blooms, its sections are shorter, and shorter pieces seem to be easier to place. In my current manuscript, the stories take longer to emerge and can’t be fully fleshed out within the typical limits of the three-to-six-thousand word submission. They are deeply layered, repressed, or difficult for Michael’s patients to articulate directly, all of which takes a bit of time on the page. These kinds of stories, the ones that surface slowly, gather momentum, and then become increasingly resonant are the ones I’ve always like to read.

Heise: In some ways, publishing excerpts from Moth was easier. While Moth is a more fragmented and experimental narrative than Night Blooms, its sections are shorter, and shorter pieces seem to be easier to place. In my current manuscript, the stories take longer to emerge and can’t be fully fleshed out within the typical limits of the three-to-six-thousand word submission. They are deeply layered, repressed, or difficult for Michael’s patients to articulate directly, all of which takes a bit of time on the page. These kinds of stories, the ones that surface slowly, gather momentum, and then become increasingly resonant are the ones I’ve always like to read.

In publishing, perseverance has been one lesson. Many online journals or journals with online components to them seem to be willing to run pieces that are longer. As with any publishing effort, finding a magazine that is amenable to your aesthetics is critically important.

Mathews: Have you found yourself revising and shaping an excerpt apart from its context in the work as a whole—to make it more of a self-standing piece?

Heise: Yes, a bit. Some of the exposition in the excerpt for Tampa Review Online is drawn from two earlier moments in the manuscript. In one, Michael attends a conference on a new sleep medicine, Nepenthe Pharmakon, that erases traumatic memories from the mind, and in the other, he walks around Berlin with Christian the day before he meets him again for lunch. I felt I needed to gesture towards those moments to help contextualize the excerpt. So a bit of cutting, revising, and rearranging was required, but not a great deal.

Mathews: One revision of your current novel-in-progress that we are aware is a change in the title. Between the time that we accepted this piece, and now, when we’re publishing it, the title changed from The Beautiful Ones to Night Blooms. Can you mention anything about your reasons for this change?

Heise: The original title amplified one of the manuscript’s main themes of obsessional beauty. But it turns out that a biography on Prince is forthcoming with that title. Flowers are a motif in the book and I wanted the title Night Blooms to pick up on some of what I hope is the darkly beautiful imagery in the novel.

Mathews: Are the locations in this book—New York, Naples, and Berlin —places that hold special significance for you? Have you lived in all three cities? What drew you to these settings?

Heise: I live in New York City and I’ve been to Berlin a handful of times. My ancestors are from there. And I’ve visited Naples, Italy twice fairly recently. They’re all important to me in different ways. In the excerpt, Christian travels to Berlin to attend the funeral of his German father, a man he never knew. I remember the first time I walked around Berlin, I was stopped dead in my tracks when I saw a store in Charlottenburg with my last name on the banner and it made me wonder what my life would have been like had my distant relatives never left for America. In later chapters of Night Blooms, Michael’s patient Sophie tracks down in Naples the descendants of one of Matisse’s models known as Lorette and referred to by the painter as “the Italian woman.” Naples is such a dense and layered city. It’s the most congested city in Europe. It’s gritty. It’s chaotic. And it’s beautiful. It seemed the right place to me to peel back the onion of Sophie’s strange and seductive encounter with a woman who claims to be Lorette’s great granddaughter, but in the end may not be.

Heise: I live in New York City and I’ve been to Berlin a handful of times. My ancestors are from there. And I’ve visited Naples, Italy twice fairly recently. They’re all important to me in different ways. In the excerpt, Christian travels to Berlin to attend the funeral of his German father, a man he never knew. I remember the first time I walked around Berlin, I was stopped dead in my tracks when I saw a store in Charlottenburg with my last name on the banner and it made me wonder what my life would have been like had my distant relatives never left for America. In later chapters of Night Blooms, Michael’s patient Sophie tracks down in Naples the descendants of one of Matisse’s models known as Lorette and referred to by the painter as “the Italian woman.” Naples is such a dense and layered city. It’s the most congested city in Europe. It’s gritty. It’s chaotic. And it’s beautiful. It seemed the right place to me to peel back the onion of Sophie’s strange and seductive encounter with a woman who claims to be Lorette’s great granddaughter, but in the end may not be.

Mathews: What is the situation or context for the excerpt we are publishing?

Heise: In the wake of his failed marriage, the narrator Michael is traveling alone for the first time in years. He is in Germany for a sleep disorders conference and is gathering stories from insomnia and nightmare sufferers for his own research at his New York City clinic, Therapeutic Solutions. Christian, also from New York, is in Berlin after learning that his estranged father died in a car accident after falling asleep at the wheel. Christian has suffered from insomnia his whole life, but it has been worsened, not only by his father’s passing, but also by a gruesome discovery he made one night when walking around his neighborhood in Brooklyn. As Michael interviews him for his growing archive on insomnia, Christian tells the story of this one night that has made his life ever since feel like a waking dream.

=======================================================================================

— An Excerpt from Night Blooms —

Two days after our initial meeting, Christian and I were sitting across from each other for a late lunch at a restaurant in Mitte that he had chosen on account of its stringently authentic German cuisine. I was in Berlin for just a few days of sightseeing after attending a conference on dreams, sleep disorders, and neuroscience hosted at a university in Essen, a dreary mid-size, industrial city in the northwestern part of Germany. On the train in, I had learned about Christian by checking an internet messaging board where those stricken by severe insomnia gathered to share their experiences. He had posted that he had not slept for more than a couple of hours a night for months, and since his arrival in Berlin from New York two weeks ago for the funeral of his estranged father, his condition had worsened. Now on even the most restful evenings he slept no more than thirty minutes in a row. Though I had planned for my brief visit to the city to be a respite from people, I also knew it was probably wiser if I wasn’t alone the whole time. So after I checked into my hotel and walked around the area until all of the stores and even most of the bars were closed, and nothing else awaited me that night except the prospect of an unfamiliar bed, I decided to contact him to ask on the offchance if he would agree to an interview. His reply—Dear Doctor Michael Eilian, I can meet for coffee—arrived ten minutes later at 3:40 a.m.

In my briefcase was a copy of the memoir Christian was writing, which he had unexpectedly thrust in my hand at the end of our first meeting on Wednesday and asked me to read. Next to us was a table of flight attendants, all women with sharply parted hair and wearing pinstriped pantsuits with metallic, space-age stripes embroidered on the sleeves and a futuristic insignia that read Star Alliance. They were getting up to leave when, as if on cue, a gentleman of about eighty in a double-breasted jacket with a rose boutonnière on his lapel emerged through a curtain in the back of the restaurant. He shuffled slowly with the help of a cane, hunched over on account of what must have been osteoporosis or sciatica, and once at their table, escorted them with his eyes fixated the whole time on their identical bright blue, two-inch kitten heels. At the door he straightened up with all his effort and shakily kissed each of the women on their padded shoulders as they filed out, one after another, five in total.

I asked Christian if he had slept the prior night.

“A bit between four and five a.m., but that was all.”

He still had on a woman’s Burberry raincoat from the last time I had seen him. The shadows under his eyes were a little deeper, hidden unsuccessfully behind concealer that I wanted to tell him to blend in, but thought the better of it. My iPhone was on the table, recording our interview for my research at Therapeutic Solutions. Over the past year or so, I had been gathering stories of insomnia and writing them up into detailed case files in order to build an archive and database to help me better understand the disorder’s psychiatric and environmental causations and its symptoms. These ranged from the common ones of mental and physical fatigue, to more unusual manifestations, including panic attacks, hallucinations, delirium, nervous exhaustion, paranoia, prolonged periods of double vision, a strange condition referred to as EHS or Exploding Head Syndrome, as well as increased risk of insanity and death. While my early psychiatric training and practice had focused on childhood memory and trauma, I had over time developed an ancillary specialization in sleep therapy and dream psychology that in the past few years had grown from a side interest into the main focus of my work and had now reached a point that it had cannibalized almost everything else in my professional life. My interest in the mysteries of sleep was partly a consequence of an extended spell of my own insomnia. It turned out to be conducive to research, since I was unable to do much else for several months after my divorce but sit at my window and think for long stretches of time deep into the night.

As we waited for our wine, Christian told me that it wasn’t the death of his father, Jens, a man he hardly even knew, that was responsible for his current insomnia. I learned that after completing his medical studies, his father had returned for good to Germany, leaving behind Christian’s distraught mother, Annabelle, in the second trimester of her pregnancy.

“I arrived too late. They were lowering him into the ground just as my plane landed.”

He told me his insomnia had been triggered by something else, something that had happened last fall.

“It was one night when I felt really restless and cooped up in my railroad apartment,” he said, “so I decided to stop writing and go for a walk. Something I did quite often. Gowanus is mostly industrial. Warehouses, shuttered bodegas, some weekend clubs in old converted factories. After sundown the streets are pretty much vacant, except for an odd dogwalker or jogger, though for years it was where prostitutes worked. Most of them have disappeared, gone online I suppose. But the empty lots are still there. And the hourly motels too.”

A waiter, dressed in head-to-toe black, brought over a dry riesling.

“It’s refreshing like the nectar of an apricot or other stone fruits,” he said in a monotone voice, then took our order, writing nothing down, keeping it all in his head like a mnemonic exercise.

As soon as he left the table, I was certain something would go awry and we’d end up with another table’s plate of sautéed spleen or boiled kidneys with mustard sauce or some other medieval German dish that the restaurant appeared to specialize in and we’d have no proof whatsoever we hadn’t ordered it.

Christian told me as he walked deeper into Gowanus that night, a front of cumulus clouds lit up by the moon was swirling in giant coils over the towers of the Verrazzano in the distance.

“Like something out of a Van Gogh painting.”

The sole motion in the neighborhood was a Caterpillar construction crane lifting and dropping metal debris and wires from one pile to another with the swing of its Sisyphean head, a small man pulling levers inside the glass box. He recounted, too, that as he ambled onto Third, the stoplights for a mile or more were yellow, frozen mid-sequence, a quirk or misfire in some mechanism, which he now thought, in retrospect, must have been the first sign that time had come, at least in his imagination, to a standstill.

Christian’s elbows were on the table, but he straightened up when the waiters were within eyeshot. He paused in his story at the arrival of a dish of spävle and a plate of grilled eel. A loaf of impenetrable black bread rested on the table like a small meteorite between us. The waiter poured water from a pitcher molded in the likeness of an aggressive chanticleer, the stream flowing from its red beak into my glass. I cut off an inch of eel, but in mid-bite decided to drink the riesling. I remembered what the waiter said about the wine and an image of an apricot tree flashed in my head. I finished my glass and looked enviously at Christian’s nearly full one. The table kitty-corner to us was now filled with doctors from the nearby hospital, still in their scrubs and lab coats, one spotted with stains down the front. I glanced at another doctor who was meticulously slicing an engorged currywurst into five pieces, from all appearances taking more pleasure in cutting her meat than in eating it. I discreteely motioned to the waiter for more wine.

Usually on his walks, he would wander along Gowanus’s notoriously polluted canal, a Superfund sewer of tar, pesticides, arsenic, even floating colonies of gonorrhea.

“People think all of Brooklyn has gonorrhea,” he said, his lips turning upwards.

The surface of the wastewater, as he described it, is coated with iridescent blooms of oil and sometimes gives off strange vapors, little wisps of smoke or fumes. You can’t help but feel sorry, he said, for the poor workers whose fate it is to pole around in the a.m. on skiffs collecting whatever bubbles to the surface—garbage bags, a seagull, a woman’s blouse, whatever else the silt releases, and terrified the whole time of splashing any water on themselves. Every summer, they find a floater, call the NYPD, who come lasso it from the bank, and if that fails, bring in a police boat and a fishing net.

Christian told me that on his walk that night, he remembered pausing as the F train trundled overhead towards the elevated station at Ninth Street. A woman, maybe in her twenties, maybe thirty, in a white dress, was walking stiffly, like her heels were too high for her, through the moving subway car until she reached the end, where she stopped to smooth her hair in the mirrorlike glass right before the train descended underground.

“I can’t explain it,” he said, “but she struck me as terribly sad. Maybe it was how the cellular windows of the car made her look like she was in a filmstrip. Maybe it was the way she smoothed her hair and looked out the window at the city but was only looking at herself, like she had done it a million times before. Like she looked out and didn’t see anything.”

His voice was breathy and low.

“Across the street,” he said, “happened to be a parking lot of tour buses guarded by an attendant’s kiosk. But on this night no one was inside, so I ventured through the lot, and on through an alley of knee-high weeds and discarded newspapers between two brick buildings, and came out on a trail along the bank. I followed the trail for a half hour, perhaps more. I had lost all track of time by this point. But eventually I discovered I had crossed to the other side of the water, probably by way of one of the small drawbridges I must have walked over without registering it.”

He told me that was when he found himself above the entrance to the flushing tunnel, enveloped by the roar of its giant submersible pump whose impossible task is to clean the canal. Christian’s voice dropped even lower. He stared at his fingers, examining each of the tiny moons rising in his shining nailbeds. A waiter appeared with another glass of riesling.

“That’s when I noticed a shallow rut in the trail, where dirt had been violently scraped away from the path down to the water like someone had been pulled or dragged against their will,” he said, still looking down. “Tilted on its side in the weeds was a woman’s Lucite heel, the plastic sparkling where it caught the unremitting glare of a cobra lamp. It had a sprinkling of soil on its straps that kneeling before it I gently blew off, along with a matted maple leaf, revealing a broken gold buckle and the number 7½ partially rubbed away on the insole. It gave off a faint heat as though it had been lost, discarded, or tossed aside no more than a few minutes ago under circumstances I didn’t wish to imagine, but which I sat there thinking about all the same.”

He paused, leaned back in his chair and exhaled.

“There was a rustle in the grass, a rat or snake, maybe a bird hopping about. And that’s when I looked up and saw her, the girl from the train,” he said. “She was lying halfway down the mudded bank, not more than ten feet from me, with her head turned sharply at a broken angle. Her mouth was partially open and she was struggling to say something, yet all I could hear was her papery breath. I walked slowly over and crouched next to her and felt like a child looking curiously at something he had seen before but was now unfamiliar and far beyond his comprehension.”

“Jesus,” I said. It was the only thing I could think to say.

“More than anything, Doctor, I wanted to reach down and gently pull back the hair where it covered her cheek, yet something told me not to touch her. Her right eyeball was pressed flat against the ground, but her left one had tightened upon my face as if I were the last thing in the world she was ever going to see. A tremor rippled through its aqueous humor, like a small earthquake inside of her, then she was gone.”

He described how blood had pooled under her, seeping into the ground, and how her short white dress scuffed with dirt was soaked red.

“I kept contemplating,” he said, “how she was ever going to bleach it clean, unable to get the thought out of my mind. She had been bludgeoned from behind with something cumbersome enough to crush in her blonde hair through her cracked tortoiseshell clip, pushing up shards of her skull. Her legs were bare, scratched and bruised with thumbprints, and one of those caterpillars with stinging spines was climbing up her calf. I watched its slow undulations for a minute, sitting stupidly in the dirt, cradling her heel, time having become gooey and elastic like it does sometimes, and I could see the moon again, huge and yellow, until it eventually occurred to me to call the police.”

Christian was looking in my direction and talking, but I sensed it wasn’t me he was addressing. He took a drink of wine and nodded slightly, as though giving himself permission to continue.

“I thought I was in some fairytale. The prince who discovers a woman’s glass shoe and dreams of its owner, searches her out forever until he rescues her. But I’m no prince. I’ve never rescued anyone in my life.” He sighed softly. “The cavalry arrived soon enough, a whole squadron of police it seemed, two of them lifting me up by the armpits from the ground with a couple of ‘attaboys.’ One of the officers pried the shoe out of my hands and looked queerly at me. They shunted me to the edge, but I could still see when they rolled her over. Her dress was unlaced at the top so the milky skin of her décolletage was visible and without a blemish, except a small strawberry mark. Her whole body was pale as though she were from some other century, like she had just had her blood drawn and was now sleeping off the effects. I would have thought that if I didn’t know she was fucking dead. Then the cops gathered in a circle, photographing her, the flashes popping, the red and blue police lights swirling against the sides of the brick buildings behind me.”

Christian fell silent, took another sip of his wine. “With the preliminary forensic work wrapped up, they stood around doing their usual laconic cop-talk, shooting the shit, scribbling notes, unfurling the yellow tape, and placing a sheet over her as if to finally put her to bed.”

“Did they question you?”

“For a couple of hours on the scene and at the precinct, swabbed me for a sample, said they’d follow up, but never did. I called back, scoured the papers, searched online for any information, and learned as much as I could, which was little.”

He looked up at the ceiling, then down again at his hands. After regaining his composure, he said, “Abigail Donnelly, that was her name. Abigail Donnelly. A student at the Academy of Cosmetology and Esthetics by day and a bartender by night. Lived on Avenue X in Coney Island. She was out to meet a friend in Gowanus to go dancing. But for some reason, she had gotten off a stop early and walked the rest of the way in the darkness. That’s all I know,” he confessed. “It’s all I know. In one form or another, I’ve been awake ever since, Doctor. Yet it all feels like a dream.”

A waiter cleared our plates and another lifted the untouched bread off the table with both hands and carried it back into the kitchen. Over a double espresso I asked if he felt guilty in any way for discovering her, because he shouldn’t. He shook his head; however, I wasn’t sure I believed him. It was clear he didn’t want to talk further about that night, so I changed the subject and asked him if he wanted to talk about the memoir he had given me, but he didn’t say anything.

“Will you contact your father’s widow while you are in Germany,” I asked. He shook his head again. We spoke for another half-hour or so, our conversation awkwardly circling through a number of other topics—how long did he plan to remain in Germany (he wasn’t sure, but perhaps for the rest of the month), was I married (I had been for five years), was he interested in visiting my sleep clinic for treatment when he returned to New York (no), what did my ex-wife Ada look like (Lebanese, her mother was from Beirut), was he interested in medication (no), did I miss her (it’s in the past, I said quickly), do you still love her (I didn’t answer).

By this time the ebb and flow of diners had dissipated and we were the only patrons left. Christian and I received the bill from another waiter, the one who had served us apparently had disappeared for the day. In the back, the host was bent over washing a chalkboard with a sponge he kept wringing out into a green bowl. The lights in the kitchen were off. In the dimness, I could discern the pilot flames on the stove burning without end and the illuminated dials of the oven. A small security monitor showed our empty table and the two of us standing next to it like dark silhouettes. The only other person in the room was a child, with nearly translucent white hair. All the chairs had been flipped up and he was sweeping with a broom towering over him. As I stood on the sidewalk trying to get my bearings, I could hear the boy lock the restaurant behind us. I turned around in time to see his pink hand lower the blinds. I don’t know why, but the gesture left a chill deep inside me and so I was relieved when Christian asked if I would like a glass of wine back at the apartment where he was staying and said if I wasn’t too tired we could walk.

* * *

As we wound our way across Berlin, neither of us spoke except for the times when Christian said “left” or “right” or “a few more blocks.” The quiet afforded me the welcomed chance to think. He seemed to me a man whose delicate constitution was offset by an imagination more lively than normal, but one that seemed to give way to melancholy, as if not only the world but the flights of his own mind inevitably led to disappointment. At first, I thought his insomnia had the hallmarks of some symptoms of dissociative identity disorder. As with many illnesses of the mind, those afflicted with it exist on a wide continuum, from mild cases of those who exhibit a propensity for losing track of time and a sense of their surroundings—becoming easily engrossed in the pages of a novel or enchanted by the rolling, sunlit fells of an oil painting, for instance—to the more extreme cases of those for whom being human remains a profoundly strange and uncomfortable notion, and who attest to feeling little connection to their own bodies and as a result are most at home in the familiar worlds of their minds. The case studies of the disorder are populated with accounts of patients who are unresponsive to the recommended treatment—intensive psychotherapy, clomipramine, periodic clinical hypnosis—and whose conditions deteriorate to the point where they feel so weightless that merely lifting up their arms or legs may cause them to feel they are floating in the air, and reports of patients who, as if they had slipped into a nightmarish tale by E.T.A. Hoffmann, claim to see themselves from across the room, as if a stranger dressed in their very same clothes has entered their house, or they feel convinced when gazing into a mirror they see not a reflection, but a doppelgänger trapped mutely on the other side of a glass wall. My sole experience with the illness was one of my first patients. In the late summer of 2001, a thirty-two-year-old investment banking analyst at Cantor Fivgerald who came to me after two other therapists had failed to help him, told me that each day as he sat on the hundred and ninth floor of his building watching data from futures markets along the Pacific Rim stream in red and yellow lines across three linked monitors, forming cresting waves and patterns of impossible complexity, he felt his body was dematerializing, and in our telephone sessions held late at night, often near eleven on his walk through the canyons of the Financial District, he would speak at length about the fact he felt wholly invisible, as if he had disappeared from reality, diminished to a spectator in his own life, as if he had died but had gone on living, seemingly despite himself.

These thoughts were floating in my mind when we came to an abrupt stop as a black Mercedes sedan with tinted windows careened around a corner nearly clipping Christian, and made me aware I had been walking without paying the least bit of attention and now had no clue where I was. Ten minutes later, we entered a concrete building with a crenellated roof on what Christian described as the bohemian fringe of Brunnenstraße. He was subletting a flat in the building from a commodities trader from Algeria named Yusef who lived in Chicago for half the year. I had never stepped foot in this part of Berlin before and would have been at a loss to find my way back to the restaurant or hotel on my own. We passed through the narrow corridor on the ground floor, hardly wider than our shoulders and which at a slight incline was shaped, as best as I could discern from our movements, like the letter S snaking through the entire edifice, and after several turns we somehow ended up on the fourth level at a door decorated with a damask pattern and a motif of pineapples in wrought iron. We entered into a highceilinged loft so cold our breath plumed in the air. The living room was a cube, the center of which was anchored by a Le Corbusier sofa and a metal coffee table with ponderous art and design books and back issues of The Economist and Monocle stacked in neat rows. Flanking the sofa was a nearly invisible acrylic stool. And above a white brick fireplace was mounted a giant ibex with two curved horns looking to me not unlike the head of some prehistoric god or alien.

The weather on the journey from the restaurant had been a watercolor of interminable gray, typical dreary Berlin this time of year, but since we had entered the building the clouds had lifted and the trees I could see through the windows had changed to radiant green. Even the normally depressing spectacle of the old GDR playground next door, a weed-filled parcel with a miserable assortment of metal bars and poles, was alive with young couples on picnic blankets tanning themselves in shirtsleeves while the temperature inside, as if another world entirely, continued to plummet. I turned around, squinting, my jacket still on, only to find I was alone and that Christian must have stepped into another room through one of the sliding doors in the walls. The traces of his life were minimal—a laptop next to a German-English dictionary and a profusion of manila folders overfilled with handwritten pages and old newspaper articles, along with a pair of black-framed glasses carved from bone or animal horn, and in the open hallway closet a few dress shirts, but nothing else except on the shelf a leather suitcase on its side with a vintage decal of a banner that read Michigan above a long suspension bridge arcing through a cloudy sky.

A beam of sunlight touched a crystal pendant suspended by fishing line in the window and suddenly small rainbows were swimming along the walls.

On the coffee table was an oversized book with a self-portrait of Chuck Close composed of thousands of pixelated cells on the cover. I sat on the couch, flipped through it, lingering over the photographs inside of the artist in his wheelchair painstakingly applying daubs of paint to a canvas looming over him. I was reading about his struggles with face blindness, which is why his entire oeuvre was dedicated to recording those closest to him by rendering them in two dimensions, the only way his brain could remember what they looked like, when Christian reappeared with two glasses and two bottles of wine, and sat down on the stool across from me.

“I know it’s freezing in here,” he said, tightening the belt on this coat, “but it’s the one thing that permits me to sleep.”

I asked Christian to talk, if he would, about his preoccupation with the woman he had found, and her Lucite heel clearly cathected with such emotional energy that it had left him entranced, paralyzed on a pile of weeds, the image seared into the retinas in the sleepless days and weeks since that night.

He crossed his legs at the knee, then straightened up in his chair, rubbed his eyes, and from a rectangular wooden box at his side, he retrieved a long, slim cigarette.

“I don’t often indulge. Do you mind?” he asked.

Before I could say “no worries,” his eyes were obscured in a cloud of smoke, as if he had exhaled his soul through his nostrils. It hung in the air until dissipating into the higher reaches of the loft. He continued this way for an excruciating minute, silently inhaling and exhaling, as if drawing his soul back in and expelling it in a continuous loop.

When he finally spoke again, his answer was as puzzling as it was evasive.

“The universe often seems to me both purposeful and random. Hardly anything we wish to happen does and what does happen we often wish had not or at least not in the way it did. Much of life, if you think about it, remains utterly inexplicable, incidental, having pivoted seemingly on the most random of events, ricocheting from pin to pin like a pachinko ball despite our best intentions.” He paused. “Do you know what I mean?”

I nodded.

He poured more red wine into his glass and took a slow drink. His face deepened.

“I once thought life would be more knowable, more lucid with each year that passed. I no longer think that,” he said. “It just gets stranger and stranger, so much so that I can only imagine at the very end one must look back and honestly wonder ‘was this my life, was this really my life’?”

After a few breaths, he asked, “You have any children, any daughters?” “I don’t.” By the time my wife and I had started to seriously plan for a family, our marriage crumbled.

“My condolences, I mean, I’m very sorry.”

He must have sensed an opening. He leaned forward with his hands steepled together and looked me in the eyes in a way that I found deeply uncomfortable.

“It is easier to be honest with people we don’t know,” he said, “Maybe it’s the only way to be honest. I live a very private life, as I’m sure you can tell.”

Christian then told me that long before he left New York to come here to say goodbye to his late father, all his relations—whether with his landlord, or the person who handed his dry-cleaned shirts across the counter, the teller at the bank in her bulletproof plastic—had a sense of finality about them, even those to whom he had just been introduced he felt he was looking upon for the last time and sensed all the more so he was remembering them from some future point that when it arrived they would be dead or gone. He told me he had learned to welcome the melodrama of these moments whose only function has been to frame time so it can be paused and studied. He said sometimes when he looked out from a bank or grocery store what he noticed were the thousands of accumulated fingerprints, each one a small maze of human oil and sometimes the smudges thickly overlapped so that he couldn’t see through the glass and at best saw simply the ghostly silhouettes of people, trees, and houses on the other side.

He pressed the wet cork from yet another wine bottle he had opened into the center of his palm as though sealing a letter or stanching a cut; then he held up his hand to show me the insignia of a hawk, its wings extended in flight, before he wiped away the stigmata with a napkin.

The air conditioning kicked on and the room felt instantly colder. Dander and dust swirled about us in the last light falling through the window and the antiseptically clean loft revealed itself as a kind of mausoleum or reliquary to memories that billowed about us like ashes.

“Without intending to do so, I’ve become a collector, not so much of experiences or even things, but a collector of what is missing, of what or who, I should say who, is no longer here but whose presence lingers behind in the residue they leave. For the past two or three years in every city or town I have visited or lived,” he said, “Philadelphia, New York, D.C., even the small hamlets in the country with a flashing stoplight and a post office, I have found along sidewalks, delivery alleys, sometimes behind roadside billboards or the rear of buildings, or on the subway at night here and there articles of women’s clothing, a shoe, or depending on the season, a scarf or glove, once a braided leather belt and a black kerchief I have only ever seen worn by widows; twice I’ve found a cobalt blue chemise—the same one, absolutely identical, once hanging from a nail on a telephone pole in Peterborough, New Hampshire, and months later when walking on Gilgo Beach on Long Island I spotted its twin buried in the shallow drifts of sand dunes. And slightly deeper in the nest of sand among twigs was a pair of sheer pantyhose, the sort once sold in large plastic eggs in places like Sears and JCPenney. The kind you might see worn by waitresses or flight attendants, you’ve seen them, right? But these were partially decomposed. On one occasion using a long-handled rake, I retrieved from a pond in a cemetery south of Baltimore a florid dress with two silk-covered buttons missing of the six that fastened up the spine and discovered hidden on its hem a monogram in silver of L.A.G. or perhaps C. I couldn’t tell for certain because of the natural decay of the water and because the koi which had been introduced to the pond to control the summer algae blooms had swarmed around it and were feeding on its threads.”

“What do you do with them,” I asked?

He rubbed his temples as if summoning a thought.

“I felt compelled for reasons I can’t fully explain to take them home with me, except I felt that they allowed me to remember people I never knew. Initially I assumed these items of clothing had been accidentally dropped, fallen from a satchel or shopping bag or unwittingly left behind, for instance, when a woman on a train removes a glove to dial a number on her cellphone but upon standing up at the early arrival of her destination fails to notice she has left it on the seat next to her. But I have since come to surmise, Doctor, that these heels, gloves, blouses, jeans, underwear, some of them split at the seams, the bodices ripped, the stitching on the dresses undone, soiled, or eaten away—were shed under duress by women attempting to flee by slipping out of their second skin into the night or were forcibly removed by another set of hands pinning them down to the earth.”

I started to say something, but he kept on speaking.

“The hosiery I found on the beach was torn, and I discovered upon closer inspection a chip of a fingernail caught like a burr in the reinforced weave of the heel. At some juncture, I realized when I was under the spell of insomnia and would go for long, meandering walks in the evening that I started actively to search rather than inadvertently stumble upon what I saw as proof of what was all around, unmistakable signs that women were missing, that the countryside, towns, suburbs, and cities of America were filled with thousands of missing women, literally thousands, their clothing stripped from them, blown about or buried.”

Christian crossed his legs on the stool and closed his eyes.

“And they are everywhere once you begin to really look,” he said, “the missing and the dead taped to front windows of convenience stores, along the sides of bus shelters between two towns at night, in rest area bathrooms, the banners in red letters—missing, please call, last seen—the date one, two, three, five, ten years ago, and on the posters their faces are ageless because they are dead and because only the living age, and because to be missing is already to be dead in a way we don’t understand yet, you understand me.”

I said “yes,” but whether I said it aloud or only in my mind, I wasn’t sure.

With his eyes still shut, he said, “you see, at times it felt like I was following these stray articles of clothing like they were breadcrumbs or threads through a maze, because I fancifully believed they’d lead me to a woman; then I could return them to her, and I would ask if she were okay, if I could help her, if it was okay if I could help her. Yet the clothing was never able to lead me to what I desired, because what I desired wasn’t out there; it wasn’t missing. Nothing is missing, if you can remember it,” he said enigmatically.

And without pausing, he continued talking as if I weren’t even there, and he recited the names of the most recent ones from the posters of missing women he had committed to memory and which I believe had become a part of his mind like the way a ghost takes up residence in the cold part of an old house—“Emma Circe Shelv of Horseheads, New York, born on the sixteenth of March 1972, was at the time of her disappearance five foot nine and a half and a hundred and twenty-three pounds with a tattoo of a heart between the thumb and forefinger of her right hand, three piercings in her left ear, and a gap between her upper front teeth and was last seen wearing a pastel yellow sweater the night of the third of January 2013 standing in her carport on Longwood Run in Sarasota, Florida; Jessica Swain of Charleston, South Carolina, born on the ninth of August 1992 was at the time of her disappearance five foot one and a hundred and ten pounds with brown hair pulled in a ponytail reaching her lower back and was last seen wearing flip- flops with sparkles on them, a denim miniskirt, and a tank top bearing the British flag on the front while eating an ice-cream cone in the company of David L. Birkett, age sixty-one, in the Mill Creek Mall in Secaucus, New Jersey, on the twenty-second of June 2013; Gina Hernandez of Chula Vista, California, five foot six and a half and one hundred and four pounds with a birthmark on her left cheek shaped like a crescent moon was last seen wearing a white sundress from Forever 21, and an anklet with a horseshoe charm with two stars on the thirtieth of July 2013 stepping into a 1971 Dodge Phoenix in the company of an unidentified male at The Million Dollar Saloon in Las Vegas, Nevada . . . Natasha Alexandra Wright born as Adam Whitcomb Clement of Paradise Falls, Arkansas . . . Abigail Michelle Donnelly of Brooklyn, New York, five -foot five from head to sole, was last seen wearing . . .” His voice grew softer and softer for several more minutes until it finally ceased. The acrylic stool he had been sitting on had completely disappeared in the darkness. He was floating in midair.

It seemed like hours had passed. I sat there not knowing what to do, feeling plunged completely out of my depth, but decided, perhaps unwisely, that the best course of action was to leave and let him remain in the sleep that had so long eluded him, the blue theta waves rising and falling with his oscillating dreams. I quietly shut off the voice recorder on my phone, pulled the door shut behind me. When I stepped out onto the street two teenage girls, dressed as if they had just left a party, were walking toward me and laughing, heels clicking on the pavement, their cigarettes burning small holes in the air. I hailed a taxi, thankful to find one at that hour, and mumbled “Hotel Auersperg” to the driver.

“How are you this evening?” he asked in perfect, if overly formal, English.

“I’m fine, I’m fine. Fine.” I leaned back against the seat and fell into silence, wishing to be left to myself.

We passed the cold blue glow of the Reichstag’s glass dome, like an eye peering up at the invisible stars. Then the Hackesche Höfe where I had first met Christian, his head bent at a table while writing something, only now the lights were off and there was no life inside. Every few seconds my face flashed in the window, but it was the face of someone older, nearly unrecognizable by the soft corrosions of time and fatigue. I felt the aura of my loneliness, which was familiar, even comforting. I lowered the window, breathed in the air that smelt of ozone and I thought it was either about to rain or snow, then I saw a flash of heat lightening miles away. The cab slowed some minutes later as it drove by the Alte Nationalgalerie and I had the sensation of sitting once more before the unearthly beauty of Caspar David Friedrich’s Moonrise Over the Sea, and I thought about what my ex-wife Ada would have seen in the silhouetted figures quietly gazing at sailboats in the distance as if would-be passengers left behind on the shores of life, the waters illuminated below by a reflected fire from the moon, at once the color of hope but also of a world that maybe in the end was both sublime and unredeemable or maybe simply wasn’t in need of us. I was sunk in a mood that had flooded over me. I decided to text her to say I’m in Germany, but as I looked at the soft white screen of my phone set to Night Shift and typed, I erased the thought, the little ellipsis disappearing on her phone somewhere. By the time she replied, if she even would, I would be home, but wherever that was anymore I wasn’t sure. All I knew was that I had a six a.m. flight from Tegel bound for New York.

We passed the cold blue glow of the Reichstag’s glass dome, like an eye peering up at the invisible stars. Then the Hackesche Höfe where I had first met Christian, his head bent at a table while writing something, only now the lights were off and there was no life inside. Every few seconds my face flashed in the window, but it was the face of someone older, nearly unrecognizable by the soft corrosions of time and fatigue. I felt the aura of my loneliness, which was familiar, even comforting. I lowered the window, breathed in the air that smelt of ozone and I thought it was either about to rain or snow, then I saw a flash of heat lightening miles away. The cab slowed some minutes later as it drove by the Alte Nationalgalerie and I had the sensation of sitting once more before the unearthly beauty of Caspar David Friedrich’s Moonrise Over the Sea, and I thought about what my ex-wife Ada would have seen in the silhouetted figures quietly gazing at sailboats in the distance as if would-be passengers left behind on the shores of life, the waters illuminated below by a reflected fire from the moon, at once the color of hope but also of a world that maybe in the end was both sublime and unredeemable or maybe simply wasn’t in need of us. I was sunk in a mood that had flooded over me. I decided to text her to say I’m in Germany, but as I looked at the soft white screen of my phone set to Night Shift and typed, I erased the thought, the little ellipsis disappearing on her phone somewhere. By the time she replied, if she even would, I would be home, but wherever that was anymore I wasn’t sure. All I knew was that I had a six a.m. flight from Tegel bound for New York.

As the driver departed, he said mysteriously, “Good luck to you sir and good night.”

* * *

Seven hours later as I was coming out of the fog of an Ambien on the flight, I realized I had forgotten to return Christian’s folder. In the seat next to me was a small boy dressed in khaki shorts and suspenders like a Cub Scout from the 1980s, his sandy-brown hair parted on the right and swept to the side like my own. His mother on the aisle. With the flimsy tray table down, the boy was intently working on a thick coloring book of extinct animals, each one drawn in its natural environment on the left and on the facing page shown in the airless world of a museum display case, along with the date that the book said, in the passive voice, that it had died out. I watched as he flipped through, searching for the next one he wanted to color. Tasmanian tiger (1936), Dusky Seaside Sparrow (1990), Pyrenean ibex (2000), Saudi gazelle (2008), Western black rhinoceros (2011). The boy searched for his orange crayon and methodically colored in the breast of a Passenger pigeon (1914), frozen in time on the end of a tree branch, its tiny black eyes alert, never to be closed.

I opened Christian’s memoir and began to read. If I were to pinpoint the date, wrote Christian, when I discovered I could leave my body by my mind alone (there is no other way to describe it) it would be the fifth of March 1994, the eve of my thirteenth birthday. That day I had received a gift from my father, the only present he had ever sent. Without warning a box had been left on the doorstep of our house, with a German stamp of a zeppelin, hovering above the skyline of Berlin. Nested inside in packthread and strips of newspaper was a volume of an elaborately illustrated children’s encyclopedia from 1912, but nothing else. No letter. No explanation. As I write this, I see myself retreating to the attic with the book and sitting in a ray of light through the window, motes of dusts floating in the air as I run my hands across an inlaid drawing on the cover of the Tree of Life in gold, its branches forming a symmetrical crown of curled lines reminding me not a little of the complex neural pathways and synapses of the brain. I instinctively held it to my face. I could smell the odor of time. As I read through the encyclopedia, he continued, I noticed it was not divided in the usual manner by the letters of the alphabet but by books—The Book of Familiar Things, The Book of Wonder, The Book of Love, The Book of Our Own Lives. And in each book were articles on myriad topics: on the science of X-ray machines, on the lives of young animals, with photographs of baby zebras and wildebeests, on whether flowers sleep at night, on electromagnetic evidence of the afterlife, on fortune telling, and on and on. What united them was a tone, perhaps unique to that brief period of history, still in the dawnlight of the new century, a tone of astonishment over the latest technological miracle and discovery, and a tone of appreciation of the enduring strangeness of the world whose mysteries will never be fully disclosed, but must always be pursued.

To this day, he wrote, I can still hear the gracefully limpid prose of the disembodied voice of the encyclopedia, a peculiar quality of being personal and yet totally detached. In fact, the language was so precise that whatever it described appeared crystal clear, yet on the verge of slipping away before my eyes. It had the ability to make me feel alert and asleep in the same breath, as if daydreaming under the effects of a strange drug. While I turned the pages of photographs of the pyramids of Giza, the port of Hong Kong, the ruins of Pompeii, as well as photographs of flowers, birds, mountain ranges, and oceans, it was as if I were in a paneled amphitheater where a professor calmly lectured, pausing briefly for the shuffle of a slide projector’s carousel. I was carried effortlessly far from wherever I might have started, he wrote, without awareness or any resistance on my part, only to find I had ended up without any sense of how I had arrived in some exotic locale for a short time before venturing on.

When I was bored or intently interested in something, he continued, which were the two moods I had as a child, I studied the encyclopedia. I would sit at my little desk with a magnifying glass in my hand, pretending I was a detective examining the people in the photographs, sometimes the pattern of a woman’s beautiful dress (I loved them even then), or a young girl with a parasol printed with orange blossoms, or a man smoking a pipe in the background. I would look and look and look as if I could find my father somewhere hiding in the pages. Of course he was nowhere to be found, of course I knew that even then, but what I learned in time was that my father, like all fathers, was less a person of flesh and blood than a way of looking upon the world from a certain insurmountable distance. A father is nothing if not a point of view. Perhaps he sat some nights in his Berlin office reading the encyclopedia before he shipped it to me and so despite the four-thousand, one-hundred and forty-three miles separating us, we had traveled with our eyes to the same distant places, had seen the same photographs of men and women and children walking through the great capitals of Europe—families now missing to history but unsuspectingly trapped in the invisible emulsion of time with the simple blink of a camera.

As I write these words, Christian continued, I see them flowing out of the shaking nib of my pen and can’t help but wonder—Where do thoughts come from?—which could have been an article in the encyclopedia. As I write, I see Abigail with perfect clarity in my mind’s eye and I see my father, too, as if they were both here alive in the room with me. And though I know what I see is only a phantom of a woman and a man I never knew, produced in the neurological theater of my brain, the little lights flickering in that black box, I still cannot help but think how those who are gone from us forever, taken away or leaving on their own volition, can be resuscitated for a little while by the medium of language. Words—they are how we communicate between two worlds, this one and the next. And in this way, as I, Christian Albrecht, a name that is not as delicate as I wish, sit alone at my desk so deep into the night it is almost morning, the scene of writing resembles a séance with those who are deceased and with those who will come after me.

“Wasser, sir would you like a glass of wasser,” the young boy, tapping me on the arm, drawing me back to the reality of the airplane. I looked up.

“Thomas, Thomas leave the man alone,” his mother said. The flight attendant with her pushcart was parked at our aisle.

“Wasser? . . . Wein? Wein? Willst du Wein?”

“Yes, wine. Danke, danke,” I said, my voice catching.

As she passed down the aisle, I caught a glimpse of a Star Alliance patch on her shoulder. The boy had resumed coloring, lost in his world of nowmythical creatures. A herd of quagga (1883) galloping elegantly across the oceanlike plains of South Africa. He was coloring their dusky stripes fuchsia and bright orange, colors that existed only in his imagination.

“You could have been my son,” I said silently, “you could have been my son.”

I propped my head against the porthole and stared out, and tried not to cry at everything and every dream that minute-by-minute was going extinct.

An hour later, we descended through the clouds into a noonday light over Manhattan.

=======================================================================================

Thomas Heise is the author of Horror Vacui: Poems (2006), Urban Underworlds: A Geography of Twentieth-Century American Literature and Culture (2011), and Moth; or how I came to be with you again (2013). He has been on faculty at McGill University and Ryerson University, and is currently an Assistant Professor at Pennsylvania State University (Abington) where he teaches creative writing and American literature. His website can be found at http://www.thomasheise.net

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.