Catch the Start of the Story . . .

You can read the opening section of “Almeda and Joe,” by clicking here.

The conclusion of the installment can be found in Tampa Review 51/52, available here.

============================================================================

Meet Robert Landry

Robert Landry is an artist and graphic designer who earned  his MFA from Tulane University. He has worked as an art director and designer in New Orleans, designed his own typeface, and served as design director for the Los Angeles Business Journal. He also founded and publishes a magazine called Crater: The Journal of a Shallow Depression. He has most recently been a visiting assistant professor teaching art and communication courses at the University of Tampa while working on a graphic nonfiction novel based on characters from his own family history. The conclusion of the first section, “Almeda and Joe,” is featured in Tampa Review 51/52. As a complement to that feature, Tampa Review fiction editors Andy Plattner and Yuly Restrepo sat down with Landry to talk about his work and the graphic novel. Their conversation began by discussing influences and background, including comics.

his MFA from Tulane University. He has worked as an art director and designer in New Orleans, designed his own typeface, and served as design director for the Los Angeles Business Journal. He also founded and publishes a magazine called Crater: The Journal of a Shallow Depression. He has most recently been a visiting assistant professor teaching art and communication courses at the University of Tampa while working on a graphic nonfiction novel based on characters from his own family history. The conclusion of the first section, “Almeda and Joe,” is featured in Tampa Review 51/52. As a complement to that feature, Tampa Review fiction editors Andy Plattner and Yuly Restrepo sat down with Landry to talk about his work and the graphic novel. Their conversation began by discussing influences and background, including comics.

============================================================================

Robert Landry with Andy Plattner and Yuly Restrepo

Restrepo: Can you talk a little bit about your background and some of the artists you were influenced by before you embarked on this project? And also can you say a little about the recordings that started the project?

Landry: Sure, if I can remember it from the beginning. Influences, okay . . . Well, I grew up overseas. When I was a young boy we moved to Beirut. I lived there through most of the sixties. In Beirut, we were exposed to different kinds of media. I first encountered my main comic book experience with Tintin, the great Adventures of Tintin by Hergé. I’ve been obsessed with him since then. I have every one of the books; I had several copies of every one of them.  My brothers and I would read them until they fell apart to get a new one. I still have a bunch of them stored away. They are some of my most prized possessions. I think if you read Tintin early enough and ingest it and digest it and let it become part of your way of thinking, you can do comics. I’ve never felt like it was difficult to make a comic because I know Tintin. You can show me a panel of Tintin, just one, and I can tell you where it is in which book—I know it that well.

My brothers and I would read them until they fell apart to get a new one. I still have a bunch of them stored away. They are some of my most prized possessions. I think if you read Tintin early enough and ingest it and digest it and let it become part of your way of thinking, you can do comics. I’ve never felt like it was difficult to make a comic because I know Tintin. You can show me a panel of Tintin, just one, and I can tell you where it is in which book—I know it that well.

So, that was my first exposure to graphic storytelling. And then when I was a teenager, of course, I got nutty about Marvel comics. Who didn’t? Really, to me, I went kind of down a wrong path. I got all hooked on superheroes and all the superhero things . . . . I don’t know if there’s something about superheroes and teenage boys that give them this sense of “Now I’ve got power.” They do this sort of—I don’t know what the word is—they inhabit the hero character in their minds because their actual world is falling apart. You become an adolescent and you figure out that the world is a pretty unlovely place, and this is when you have your first crisis about war and existence and impending adulthood and girls and all these things you can’t figure out.

When we left Beirut, we went to Nigeria, just in time for the civil war, and we were there for a couple of years. That’s when I started reading mostly American comic books. Every year we’d come home on leave, and I’d come back with a stack of comic books. . . . I didn’t have much art education. That’s another thing. I had a little bit of art overseas, but in high school—this is when the American education system starts turning to crap, and I didn’t even have art classes in high school. Then, oddly, I go to college and they’re asking me what I want to do for a major and I thought, “I don’t like anything except to draw, so I’m going to major in art.” That’s when I first started seeing art. I didn’t know anything about it. Only at LSU did I start to begin to see that there was a big art world out there, and that art is a much wider phenomenon than what you thought as a kid in a small town in Louisiana.

Restrepo: You did painting for a while.

Landry: I majored in painting. As I say in faculty introductions, “I got a masters in painting and drinking,” which was pretty much what it was. That was a pretty hard crew in graduate school. What was fun about that was that I learned that artists really are committed to that life. Experiencing committed artists was another eye-opener. I always thought, “Yeah, I can do some art and have a job,” but I met people who had no conception that they would do anything but be artists. That scared me, and I didn’t do it. I went into newspapers. I actually started in newspapers as a typesetter, so there’s that parallel track: writing and wording and picturing going side by side. I only worked intermittently as an artist and a painter in my adult life.

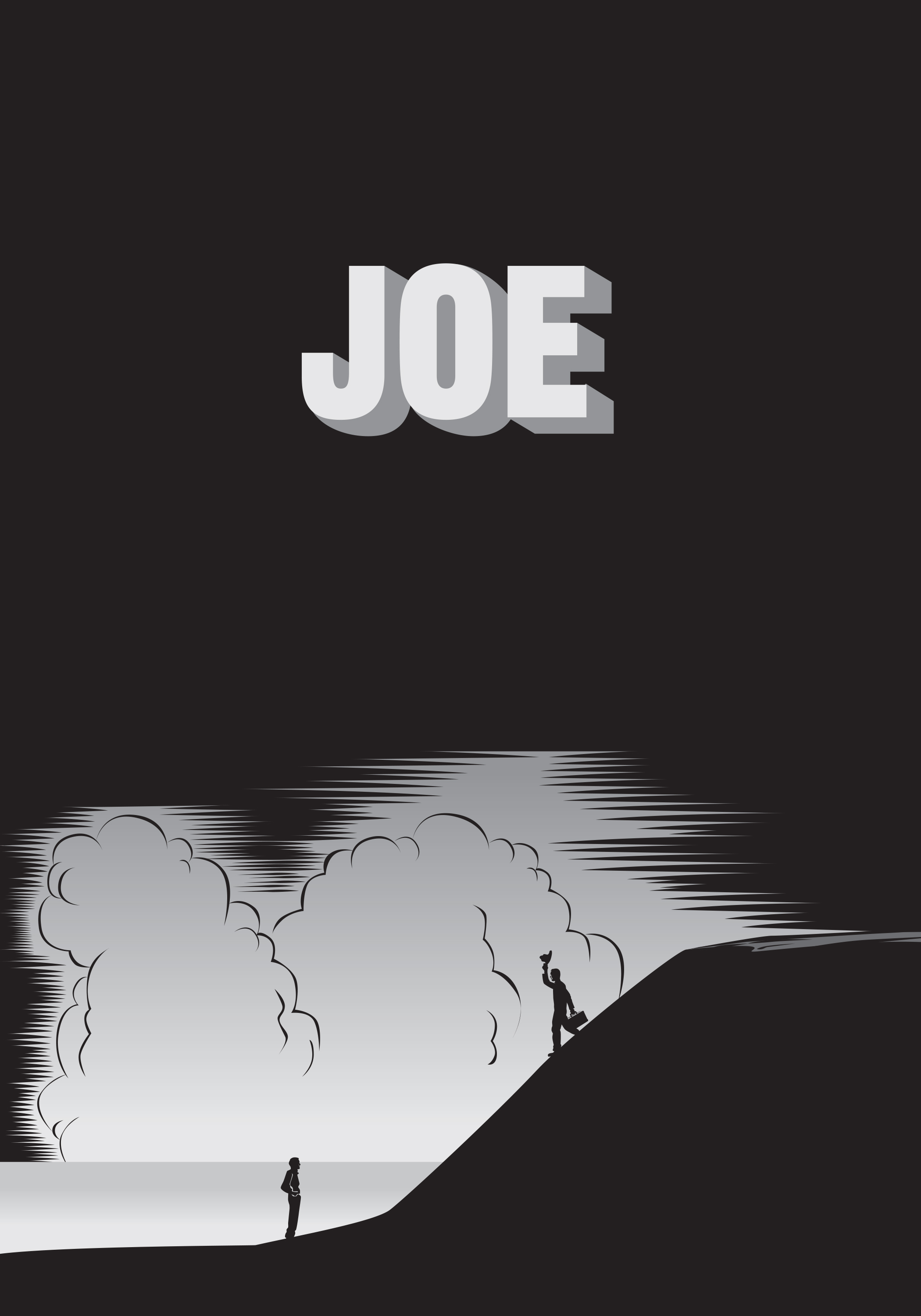

Title page of “Joe”, part two of the series.

But, you were asking me about the tapes . . . Well, the tapes were from my aunt, and they were tapes of my grandfather on his deathbed. He got very sick towards the end of his life; he had cancer when he was sixty. It got worse and led to other problems, and he collapsed and was in the hospital. We were hearing that he wasn’t in good shape. He kind of recovered, but then he died soon after being released from the hospital. I say he was on his deathbed, but he didn’t die there, he died shortly afterward under some fuzzy circumstances. Aunt Gloria, who is our excellent family historian, decided that what we needed to do was to get Joe to talk into the tape recorder. It was a revelation that she had, which might have been influenced by the fact that I did that once with my other grandfather for an oral history project when I was at LSU. I bought a tape recorder and listened to my father’s father talk about his young days and the Depression. I have a transcript of that, too, somewhere . . . . But Aunt Gloria brings in a tape recorder and starts talking to my grandfather and asking him questions. In fact, one of the things about the tapes is that she’s asking questions and he’s talking and he starts to ramble—and that’s kind of where the richer stuff is. Meanwhile my mom is transcribing. She transcribed a lot of what he said. Later she typed up her transcripts and gave them to me, so I had that for a long time. That’s what “Joe” is: “Joe” is this transcript that my mom made of what she heard in the tapes and what she heard in the hospital. However, those tapes are interesting because there are four of them and there’s a lot more on them than just “Joe.” One of them is of him singing, singing songs he learned when he was a boy in Oklahoma. He was a singer. He would sing with bands and stuff like that. He was a polymath—he could do all kinds of stuff.

So, he talks into the tape recorder prompted by Aunt Gloria and Mom. Aside from the songs, there’s also a long work history, very long, very dry, but it has usefulness as a record. He also went into some other stuff, which was mostly Aunt Gloria asking questions that she had some fixations on that didn’t relate to anything in the past. She was asking him questions about things that were going on then and there. But one tape especially became the basis for “Joe.”

Plattner: Harvey Pekar and Robert Crumb are two famous comic strip writers who often draw on autobiographical elements for their stories. Their work seems honest to me; they also seem to be driving at something, at least in the comics I’ve seen from them. Do you view your work this way?

Landry: Well, in the case of “Almeda and Joe” I don’t have much choice about honesty. I’m not going to leave anything out. Since I am working from fact, it doesn’t make any sense to do that. Of course, there is obviously way more happening in their lives than what was given back to me. But I guess the basic outline is true, and you can’t fudge it; it won’t work. In the case of “Almeda and Joe,” the whole basis is nonfiction. So I pretty much have to put down what I have been given. The only time I felt like I had to maybe mold or tweak the story was if I felt there was a part missing or if I needed to add something so that the reader would be able to make sense of the sequence of events.

Restrepo: Helping readers make connections?

Landry: Yes. You know . . . I’m trying to think of what would be a good example. The business of Joe going through an annulment was something that different people remember differently, I found out. What I decided to do was . . . I had to add to it. What I’m thinking about here, specifically, is the jaw-breaking incident in the story. When I talked to Deana, who was the daughter of Joe and Almeda, who by the way I did not meet until I was a grown-up, I didn’t even know about her until I was a grown-up—

Restrepo: —She’s the one who left with Almeda, after Almeda and Joe split up, right?

Landry: Yes. She was Almeda’s daughter; she left with Almeda. She’s about the same age as my mother—well, she’s a little younger. And I said to her, “Well, gosh”—and as we were talking I wanted her to know what I was doing and Gloria was very good about this. She said, “You gotta let people know what you’re doing, talk to them. Nobody should be surprised by this.”

Okay, so I called Deana, and I did compare some notes with her about what I knew. She basically confirmed everything, but she also talked to me a lot about Almeda, who turned out to be an extremely interesting character. Almeda ended up being married seven or eight times.

Restrepo: Just in the section we have read, you can tell that she’s pretty interesting.

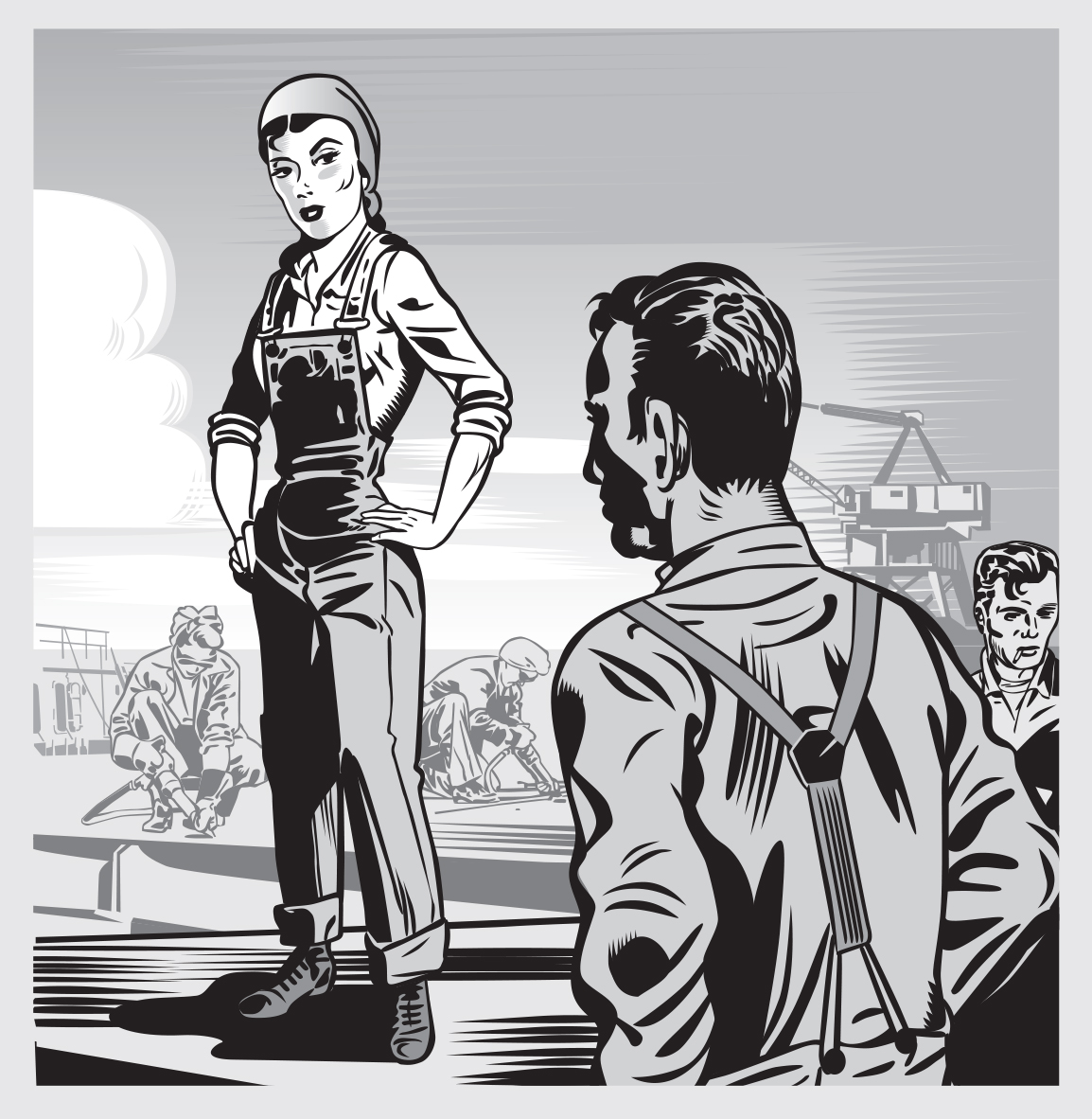

Joe and Almeda meet while working at the shipyard.

(From “Almeda and Joe”)

Landry: Our family seemed to generally think, “Oh, Almeda was crazy; she just married men” and this, that, and the other. But Deana had a different way of expressing it. She said, “My mother was a free spirit who was ahead of her time.” And the way she describes Almeda, it makes more sense—Almeda was a carnival roustabout; she did things at the carnival that guys did, so it was nothing for her to move over to the shipyard and become a riveter. And the other thing she told me was—I said to her, “Deana, I guess when Joe found out Almeda had two other husbands that was really what ended it.” She said, “Well, yeah, that was part of it, but what really did it was when he broke her jaw.” I said, “What?” And this was a surprise, but what it also did was it made Joe a little more three-dimensional. Joe, if you leave out this business of him being this person who could be violent . . . it looks like Almeda is this, you know, almost like a tramp, and it’s not right. They were complicated people with complicated lives. When Deana told me this, I said, “Tell me more,” so she described the whole situation to me, and I put that in there because I felt like it needed to be done to keep Almeda from being a completely unsympathetic person. Because I don’t think she was. I think she was, like Deana said, a free spirit. She married these guys and moved in with them and was with them, and when it didn’t work out she’d get a divorce or just leave. She’d go be with some other guy, but she’d marry him! She sounds like Elizabeth Taylor: she never slept with a guy without marrying him. So maybe that’s what Almeda felt—like what she had to do. So, how did we get to this point, though? We were talking about truthfulness in narrative . . .

Plattner: Are you surprised by the dark nature of this story?

Landry: I don’t think so. It didn’t strike me as a dark story as much as an eventful story. We always heard these legends about my grandfather when we were kids. —Okay, we need to step back for a second. What this is really about, to me, this project, is getting a story straight that our family can have. I’m really chronicling it, so it didn’t matter to me if it was a good story or a bad story or anything. It’s our story, and I wanted to get it right. I was able to do so by consulting these other sources—some people that are still alive, some that had tapes. So I think this is as truthful of a story as I could get, and I still feel like it’s worth looking into. There’s a lot of stuff that happened. It’s just like any other family, but the story itself I thought was really worth attempting to put into a graphic novel. And I feel vindicated on another level as I move into Part Three. There’s just as much in that part that’s going to be interesting to people. Part Three is quite engrossing. Without doing spoilers, I have a bunch of newspaper articles, and sheriff’s reports, and coroner’s reports, and other newspaper stories about gunfights. And this is about my family going another generation back: my grandfather’s parents’ generation.

Restrepo: So what does it mean to you to do this family story justice? You were saying you were writing this because it’s your family story and you want to be truthful to it and you want to represent it in a way that honors what the people were really like.

Landry: I’m not sure I understand the question.

Restrepo: What do you feel is your responsibility in telling this story in a truthful way?

Landry: So, I feel like this needs to be done because . . . I’ll give you one example: I called my brother a while back, and I said, “Did you get your copy, this latest issue of Crater, a little self-publishing thing?” And he says, “Yeah!” And I said, “Did you read it?” And he says, “Yeah! I didn’t know that stuff.” And I said, “What?” He says, “Yeah, you know, nobody ever told me anything.” . . . and this is my little brother. And what’s coming out there is, you know, he was too little, and nobody bothered talking to him about stuff. I was older, and I got some of these stories, and I’d hear them and stuff like this, and I guess maybe he’d be off somewhere playing. All that in one gulp. Even I did not know all of it. And then it occurred to me: all over our family, nobody knows the whole story. Me, and Gloria, and my mom, who is now gone, and my uncle Bobby—they know. But none of their kids and my children really know, so it’s the grandkids and then the great-grandkids who are in the dark. The only place they’re going to get the stories is from one of us. So I thought, I’d better do this—and I better put it in a much more digestible format. I could do a book, and it would be this nice little book of the Lewis family, and, really, ten people would read it. I really think my family would like this, and I think that it’s got enough going for it that it’s actually interesting to other people. And I managed to get it out by word of mouth to friends, and they do like it. And so I feel like by doing it this way, I’m doing justice to the story.

Plattner: Do you think that class is a strong theme in the works you’ve done so far? Economic class, I mean.

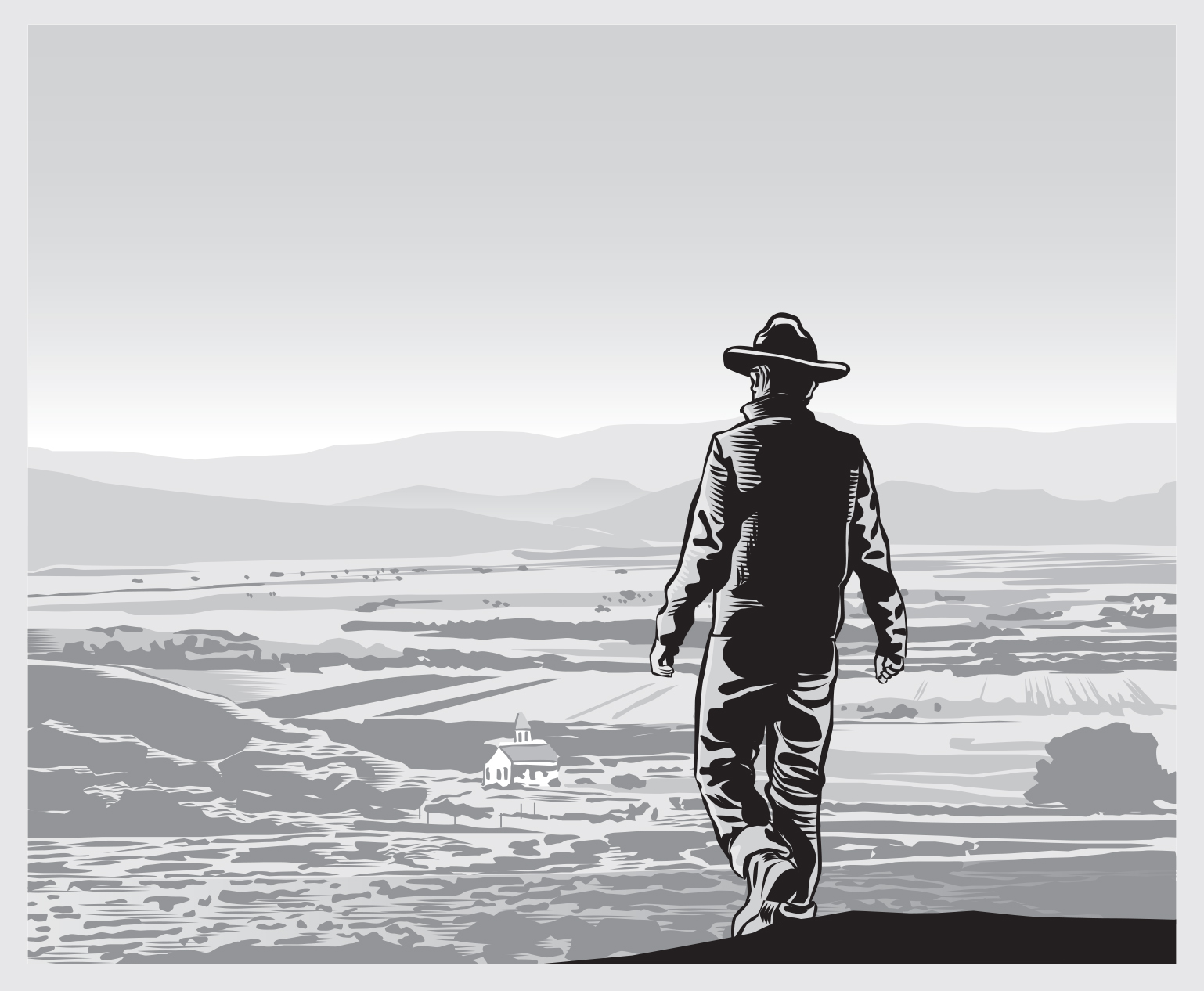

Joe crossing heavy terrain to attend school. (From “Joe”)

Landry: No . . . Maybe somebody else will come along and look at it and say yes. But I will say this, though: what I’m conscious of is that this is a story of a white male, mid-twentieth century man. And I can’t change that, so that’s the story. And what happens to him—it’s emblematic of a certain type of thing. And really, you know what, I think it’s not going to be around very much longer. He was a working guy in a place in time when the country was still more or less low-population, comparatively speaking. There were fewer minorities, and he still was privileged in a way that was pretty stark. He was able to just walk around the country, hitchhike—everything—without worries. If he had been a black man, the story would be totally different. So I guess I mean yes and no—the story’s the story. I don’t have a social agenda about it. I was trying to be as truthful as I could with everything.

Plattner: Did anything about the completed work surprise you?

Landry: No, no, I wasn’t really surprised by anything, mainly because I had Joe’s recordings, and the transcriptions. It was something I had had in possession for a long time. The only thing that surprised me a little was his way of being; kind of matter-of-fact about certain things. He says, “I had all this money when I got back to New York. I was gonna go back to Colombia to marry this girl because I was in love with her,” and then she disappears from the story. He spends all his money, gets drunk, he can’t find a job, and then the Depression hits. Those abrupt changes, maybe, are surprising. You know, surprising because most of us went to school, graduated, and we found a job. We started a career, and maybe twenty years later changed jobs, you know? We moved along on a track. In Joe’s case, though, he took, pretty much, whatever was in front of him and had no choice in some regards.

Plattner: Okay, that’s interesting about your work. You tell me if I’m getting this right, but it’s almost like there is no emotional inflection at all. It’s just like, “this happened, this happened, this happened, and this happened. This didn’t break my heart; this didn’t make me suicidal.”

Restrepo: I think that starts to happen at the end of the “Joe” section. And even so, it’s very muted.

Landry: Yeah. Okay, that’s a great observation. He’s this Okie, and he really was a tough guy. And, well there’s a couple of things going on there, too, that you don’t know about just reading “Joe.” Talking about Irene, his wife, he claims, and he says it on the tapes, “I did not know she was that sick,” and “I did not realize that this last pregnancy was so hard on her. . . . She was always smiling; she was always happy, and for her to die like that was a big surprise.” Those are some of his words. The ones I put in “Joe”—that was in one part of one tape, he had a few seconds of talking about it somewhere else that basically repeated, but they were just different words. The upshot of it was that he was surprised by it. What that brought home to me was that it was a much more stoic time. In those days, working people didn’t have time to go to the doctor. Irene’s sister, Beulah, was a nurse, and Beulah did do things to take care of her, watched over her and assisted in all her births. In fact, by the way, Beulah was the attending nurse in the birth of all three of the boys in my family. She was a nurse for years, and years, and years. So she was always there as an attending nurse in my generation and the previous one. For him to say it like that, though, was the strongest emotional point in that narrative. So I used exactly what he said. I used the pauses and the “uhs” and the “ums” because that was the most, to me, riveting event, and it was the perfect ending for that section because she dies and “Almeda and Joe” starts when he was a widower. So that is a perfect kind of way to segment this. And death plays a part in Part Three, too. Death follows this story around. That’s maybe really what people should be looking for. That’s inevitable—people die. Where they fit into the family narrative, to me, is what makes this story interesting.

Restrepo: I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about how you approached the art in “Almeda and Joe” and in the section called “Joe.”

Maxine

(From the first page of “Almeda and Joe”)

Landry: Okay, the art was a very difficult thing. Because the way I rendered art in both of these chapters is really not the usual way I work. I tend to do a little more of a simplified type of illustration. But this is World War II, and I wanted to have this kind of retro feel to the imagery, so I worked black and white, first of all, to date it. It would have been maybe even better if I had done a sepia-toned thing, but I think that might have been just a little much. I didn’t want it just to be an old-timey, grainy kind of imagery. I wanted it to just look a little more forties, since “Almeda and Joe” takes place in the forties. So I did a couple of things. One of them is I used this black—heavy black—rendering style that looks like brushwork. It isn’t brushwork, though; I don’t work in ink. I do pencil sketches, but then I scan them and re-render them in a drawing program on the computer. In Illustrator. Mainly because I’m the world’s worst renderer. I mean, I’m really not very good at drawing. I’m very good at re-rendering. The beauty of working in the computer is that you can take everything back. You can go all the way back to zero and start over again. So, you know, I’ve worked very hard at trying to get this rendering style to look like this lush, inky style so that I can strike the right note, the right atmosphere. Now the other thing I do is a lot of research. None of the pictures in “Almeda and Joe,” except my mother’s, are from actual photographs. My mother’s image is from an actual photograph of my mother, but everything else in here is just me reworking old comic book panels, adding/subtracting figures. I’ll find a picture of something that I like for its composition, but it’s modern, so I change the dress of the characters, or if I like the expression I borrow the expression, but then I date the figures with hairstyles and things like that. I did a lot of research on clothing, cars . . . . There are pictures of bars that I just kind of borrowed from photographs from the Depression. I did a lot of looking at Depression-era photographs.

And then another thing I did was to re-draw my memory of what my grandparents’ house looked like. This is pretty much how the house looked that they lived in. In fact, it’s still there. My Uncle Bobby lives there now, the oldest boy. They had these doors with this rounded framework in the house. Here’s the funny thing about this, I showed this to my Aunt Gloria and my Uncle Wayne and my Uncle Bobby—and these are all pretty much made-up interiors and exteriors—and they all said, “That’s just what it was like! That’s just what it was like!” So what that tells you is that memory is selective, and you can make a very resonant set of images even without exact verisimilitude. So when they said that, I felt very good—“Okay, I got this right”—because the story’s truth is there and you have to work this behind-the-scenes stuff right to get the atmosphere right. There’s a photographer, I forget his name, but he said something like, “There’s facts and then there’s truth.” Facts can always be changed around, but how you approach the truth is how your work is going to be looked at.

Restrepo: I was just wondering if you were going for some specific feel in your rendering of Joe?

Portrait of Joe.

(From “Joe”)

Landry: This is a great question. The whole time I was doing this I thought, “This doesn’t look like Grandpa Lewis.” So I kept trying to tweak the features to try and approach what he looked like. I eventually said, “To hell with it.” He was a big guy; he was a redhead, and he had a receding hairline, and I thought, “I’m just going to go for that wide of a range.” I don’t want to take pictures of him, and pictures of him, and pictures of him to where every little fold of the eye is right, the exact shape of his nose, every turn of his lips—you can’t do that. I realized I was right when I read Scott McCloud about comics. He said, “There’s amplification through simplification.” So, I thought as long as I got somewhere in the ballpark of the curly hair, receding hairline, square-jawed Okie, that was gonna do it. And again when they got this, nobody sat there saying, “That doesn’t look like him.” Nobody did that. They said, “Oh my god; oh yeah, this is what he did next.” I remember this, and like I said, Uncle Bobby or Aunt Gloria, I forget who, but that’s just what it was like. That was the thing they kept saying. So I said, “Okay, I got it right on two levels.” I didn’t have to get a photographic likeness every time. And you know what? It would be really artificial. It would look almost like you stuck a photo on a drawing if you got too far into getting the exact features.

One of the things about using Maxine like that was I wanted two things: I wanted to honor my mother, and kids are easy to do. I could get her and then move on. And really if you look at kids in the next page, the first two pages of “Joe,” they do look like pictures from them as kids. There I did put pictures on to the screen to work from them, but then simplified them a little bit. But I did try to get closer to what they looked like. Again, kids’ features are a little less developed, so you can get it and still be simple. You want to get faces more or less simple.

Plattner: It’s also you telling the story now. It’s interesting how you talk about the way the man looks, because that’s not exactly what he looks like. You’re seeing something a certain way. You’re bringing your own fingerprints to the telling of the story. That’s what’s going on, right?

Landry: Mm-hm, yeah, absolutely.

Plattner: I was going to ask you about story-telling influences. Were you influenced as a storyteller putting this together? Does Hemingway or anything literary creep into that?

Landry: Bukowski. It’s a funny thing. Reading Bukowski and then hearing this story about my grandfather, especially when he was a young man into the twenties and thirties, a lot of it sounded like something out of Bukowski. And so reading Bukowski, especially when he was a tramp and a bum, it’s obvious that he worshipped Hemingway. Even though he disdained everything, he still had his own secret hall of fame with Hemingway in it. This short, abrupt way of storytelling, especially in the story of Joe and Almeda . . . yes, Bukowski would be an influence—and Hemingway too, obviously.

Plattner: Why do you think Bukowski stands out there?

Landry: He was always an outcast. His sense of things was, “Why fight it.” To him, honesty is this talisman because he is confronted with so much of the ugliness and the hypocrisy of the ‘normal’ world. With my grandfather, I think it’s very different. I think his vocabulary is similar, especially his own talking, but his influences are more from a day and age when men were not emotional and demonstrative and things like that. Like you hear all about the guys who fought in World War II: “What were we supposed to do? We got drafted and we went.” A lot of people don’t know that if they would investigate a little bit, they might find how unpopular the war was with a lot of people. They didn’t want to do it; none of them wanted to go. Anybody that could get out of it did. That isn’t very well discussed, because most people said, “Well I can’t get out of it, so I’m gonna go.”

To get back to Bukowski, though, I think he really worked at this, worked at narrowing things down to their essentials. I wanted to get back to Bukowski for just a second because when my grandfather talked about when he got married, I thought, “This would not look wrong in a Bukowski story.” He says “We went down and got married” . . . . “We came back to her mom and dad’s and told them we’re married. Then we went down to the motel and I couldn’t perform.” I think if Bukowski saw this, he’d steal it. It’s just too upfront – it’s too plain.

Restrepo: I was curious about the difference in the narrative between “Almeda and Joe” and “Joe”. Because in “Almeda and Joe,” there’s almost always one panel per sentence, whereas in “Joe” you have a whole paragraph paired with one image on each page.

Landry: Well here’s the problem: that’s strictly a problem of physics. If I had done “Joe” the same way I did “Almeda and Joe,” it would have been about one hundred pages. I would have had to do four or five images for every image I did in “Almeda and Joe.” It really would have gone on long, and I think a lot of the illustration work would have become a bit of a chore, not just for me, but for readers. I think that if I had tried to illustrate that thing top to bottom . . . I just don’t know if anyone would be able to hang in there. With “Joe” you can read it, and, again, you have amplification through simplification. In this case, it’s giving the reader enough narrative for them to make up some images on their own to go between the images I gave out. The images I picked to do were pivotal each time, and then the rest of the story kind of goes around it, like water around rocks. . . . It was a different method. The illustrations are much more considered, and I let the rest of the narrative go around it.

Restrepo: Just finally, very quickly, is Part Three going to be the final part?

Landry: Yes, because basically what this is is . . . “Almeda and Joe” is the end of the story. He comes home from World War II and really it becomes a normal family. He marries Beulah after about a year of courtship. They raise the kids, they all grow up normal, they all have kids and everybody goes to college, everyone becomes upright citizens and all. Really, my family knows this part of it, we all know this part well. So this is where I stop it. The reason I’m going so far back in Part Three is that, again, this is a section of our family history that nobody knows. Nobody knows this, nobody knows that . . . Even my Uncle Wayne, the youngest one, when I told him about what I was writing about in Part Three said, “I didn’t know that.” I said, “Your own father didn’t tell you about what happened to him as a young boy?—or what happened to his mother?” He said, “No, I didn’t have a relationship with my father.” By the time Wayne was growing up, Joe was working in Venezuela again to make money for the family. In that regard, yes, the family was a little dysfunctional. Wayne and my grandfather didn’t really get along. They didn’t have a knife fight or anything, they just didn’t have a good relationship.

I feel like the early part is what’s interesting and what needs to be told. If somebody wants to come along later, like my son or his son and say, “Hey, what did you do when you were a kid?” I’ll tell him he can write it down if he wants. Who cares?

============================================================================

The opening section of “Almeda and Joe” can be found here. The conclusion of the installment can be found in Tampa Review 51/52, available here.